PORTRAIT OF AN ORAL HISTORY BETWEEN

KARION LIU & THEODORE (ted) KERR

A.

He is an artist and I am a writer. We call each other Kai and Ted. We are both short, cis-gender, gay men. He has black hair. I don’t have hair. We are from different parts of the world. I am from Canada, he is from Taiwan. But we both grew up in complicated families where violence was present and we both like cinnamon raisin bagels topped with vegetables. We are about a decade apart in age, with Kai being born after me.

Kai went to school in Taiwan to study photography. I went

to seminary to look at ethics. But, we both make work about HIV/AIDS and use

oral history as part of our process. We both understand that since no one gets

HIV alone, no one should have to deal with it alone.

When Kai asked me if I would do an oral history, with him

as narrator, I said yes. I got us a room at the school where I teach; we set a

date, and we met.

We both had a cold on the first day of our oral history.

Kai wonders if I gave it to him or if he gave it to me. It does not matter to

either of us since we are both excited to work together. Before we start

recording, we gossip. Kai eats a bagel.

On the second day of the oral history, he brings cough

drops and anti-mucus pills. He

shares. 30 minutes into the interview I feel tired. I ask Kai if he is also

tired; I wonder if the pills have made us drowsy. He says, ‘not really.’ I

don’t

believe him. 20 minutes later I feel less tired. I always forget that doing

oral history can be draining.

During

our interview Tree is there, and Tree’s darkside. Tree came to Kai after the HIV diagnosis. Kai

was in meditation (at a good friend’s urging) and in that state Kai could feel Tree. Later, Kai

began to feel Tree’s darkside.

So, for the oral history, there were four of us; me in my body, and everyone else sharing Kai’s. In the transcript, the idea of who is talking is confusing. There are no names assigned to what was said. Sometimes, during the interview, I spoke assuming Kai was not answering. Most often answers came in the form of third person from Kai and Tree—seldom did I hear directly from Tree’s darkside. Sometimes I asked who was talking.

B. TRANSCRIPT

In the beginning, I didn’t see… Karion Liu didn’t see Tree as a human form in the image, but I did see … Karion did notice there is a river and beside the river there isa tree but the tree already been cut off, so only the root left there. Karion feels down whenever he sees this vision, and he saw this a couple of times.

Because he just saw the root?

Because it’s pretty evident that Karion causes this. He cut the tree and this is how they understand it. The other image is Karion saw the tree is in the factory and the factory has artificial grass, plant and the tree cut off, someone put it in the middle of the green.

The real tree is put in the fake grass?

Yeah, in a factory, with a rolls-up-and-down gate like at a bodega. It opens automatic, and I see the tree in the middle of the factory, isolated, the gate will be closing down while I am waking up from the meditation. This was after I was feeling better, while Karion Liu’s mental status was getting better.

Wait. Who do you think is talking right now?

Both.

Okay, not a third?

“Not a third?”

Is it a third person? Is it a different being that’s talking right now,not Tree, not Kai?

Yeah, maybe it’s a third person because he is trying so hard to make sure I’m using the right term. After Karion Liu feels better, he started seeing Tree as a human form, a child beside the river. Then he realized, the river is actually the memory of his life, and it keeps flowing but also as a loop. He saw Tree playing with the river, or maybe just staying still beside the river and touching the water. Karion tried to talk to Tree, so he knocked Tree’s shoulder but Tree refused to turn. I guess that was the only time that Karion sees Tree in human form. And then Karion found out there is a new leaf, a little tree growing on the roof, but recently Karion can’t see any vision about it. I don’t know what’s the reason about it. Maybe it’s because he just too tired to mediate or he is not taking care of both of them well.

C.

Oral history is a relatively new discipline, and as such,

has flexibility. One of the coalescing voices of the tradition is Alessandro

Portelli, who, in his essay, A

Dialogical Relationship. An Approach to Oral History states that when we

speak of oral history we are speaking of a historian’s tool, “in which questions of

memory, narrative, subjectivity, dialogue shape the historian’s very agenda.”

Within this broadness, there are some shared ideas. For

one, the concept of the interview is vital. Oral history as source and process

is about conversation. It is an exchange, and often a series of compromises

between what narrators want to share, and what interviewers are aware of or

interested in having be part of the record.

The idea of listening is also key. Portelli himself says, “Oral history, then, is

primarily a listening art.”

So much of what I do when I am

sitting across from someone is thinking about the layers that are being shared

in voice, silence, gesture, action, word choice, etc. I am listening,

reflecting, anticipating, crafting, hosting, holding while also trying to ensure I am not blocking or impeding any

expression.

Maybe less obvious, when it comes to oral history, is this shared if not agreed upon idea of narrative. While not always obvious, the narrator and the interviewer are making and telling a story. Sometimes a listener will find something like a single plot, with clear and reoccurring characters, in a finished oral history. But most often the narrative that is crafted and recorded is an assemblage of never-before-shared memories, epiphanies and often-told stories that give shape to a life.

I would not understand such things about oral history, were it not for what I would call my introduction to the feminist tradition through Suzanne Snider at the Hudson Oral History summer school. Through her teaching I was exposed to a method that prioritizes listening, support, and collaboration. I see my job as an oral historian consisting of performing tasks to provide a foundation for the narrator to record for the future an understanding of the past in the present. I make possible conditions of trust and communication for the narrator to be nimble, self-aware, self-reflective, and open to co-creating history with me through the lens of their experience.

That means considering what space, place and atmosphere

suits the person and the goals. Sometimes it means “showing up” with a recorder. Other times it is about negotiation, and a

lot of back and forth. Sometimes it is

about making sure that’s someone has a chair which accommodates their bad back,

sometimes it is jumping through emotional hoops to illustrate I will not be

emotionally abusive in anyway.

In the process of interviewing I listen to the narrator for

where to go next, based on: what is being communicated (through words spoken

and unspoken, and body language); my own curiosity; what I think history needs;

and what I think the future might be interested in. When I am not sure where to go next, I stick

to questions that illuminate what was just communicated, or I follow

chronology, based on western ideas of time.

Other than that, I don’t have any rules when performing oral history, although I

have a few standard questions. Early on I like to ask: What is your earliest memory?

People’s responses provide information I can always follow up on

later, such as setting, and how someone saw themselves early on. I hope it also

provides an opportunity for the narrator to worry less about facts and more

about what images and memories they have long held onto that they want to

share.

I also like to ask: Who is in the room with us? Sometimes I clarify what I mean by “in the room.” But most often the narrator will find their own definition. They will talk about guardian angels, and ghosts, or they will talk about future audience or loved ones in the next room. Kai, in his oral history, spoke about Tree and Tree’s darkside. It was a way of preparing me to listen for who was speaking, and an invitation for Tree and Tree’s darkside to feel agency to share and be present.

Often towards the end of an interview, I will ask: is anything you want to say that we have not touched on? I think I learned this from Suzanne. For me this as a last question has resulted in long answers, with new or clarifying information being shared. But most often it results in a big sigh and acknowledgment of what was just shared. I think it is good, and ethical even, to capture the narrator’s experience of the oral history process, if only in the sound of their recorded breath.

D.

If you listen to Kai you learn that he does not have HIV,

Tree does. But still, Kai is the one that is made to carry the burden. During

the oral history a lot of blame was being placed on Kai. This upset me, so I

asked:

Why are you taking it out on Kai when it is not Kai’s fault… HIV is nobody’s fault, or HIV is the fault of the state who doesn’t provide medicine or the…

I was cut off. A combination of Kai, Tree, or Tree’s darkside

respond:

I don’t think my concern is only on HIV, my concern is more about… He is supposed to take care of both of us our body…

E.

The oral history Kai and I did together was part of his

larger project called Humans as Hosts. He uses oral history (and portraiture) to create conversation and further understanding about

the ongoing AIDS crisis, through the lens of people living with HIV. He started

the project in Taiwan. He interviewed his friends, and other people he knew,

making pictures of them, with them. In these early photographs, faces are

obstructed. HIV related stigma is still strong in his home country. People feel

they can’t

share their status publicly. This is something Kai, Tree and Tree’s darkside understand.

The oral history is integrated to the process of taking the picture. Often objects that appear in the final image, are one mentioned in the oral history. They are done, often together, over the course of a few days spent together. The process of the photo and the oral history are not separate.

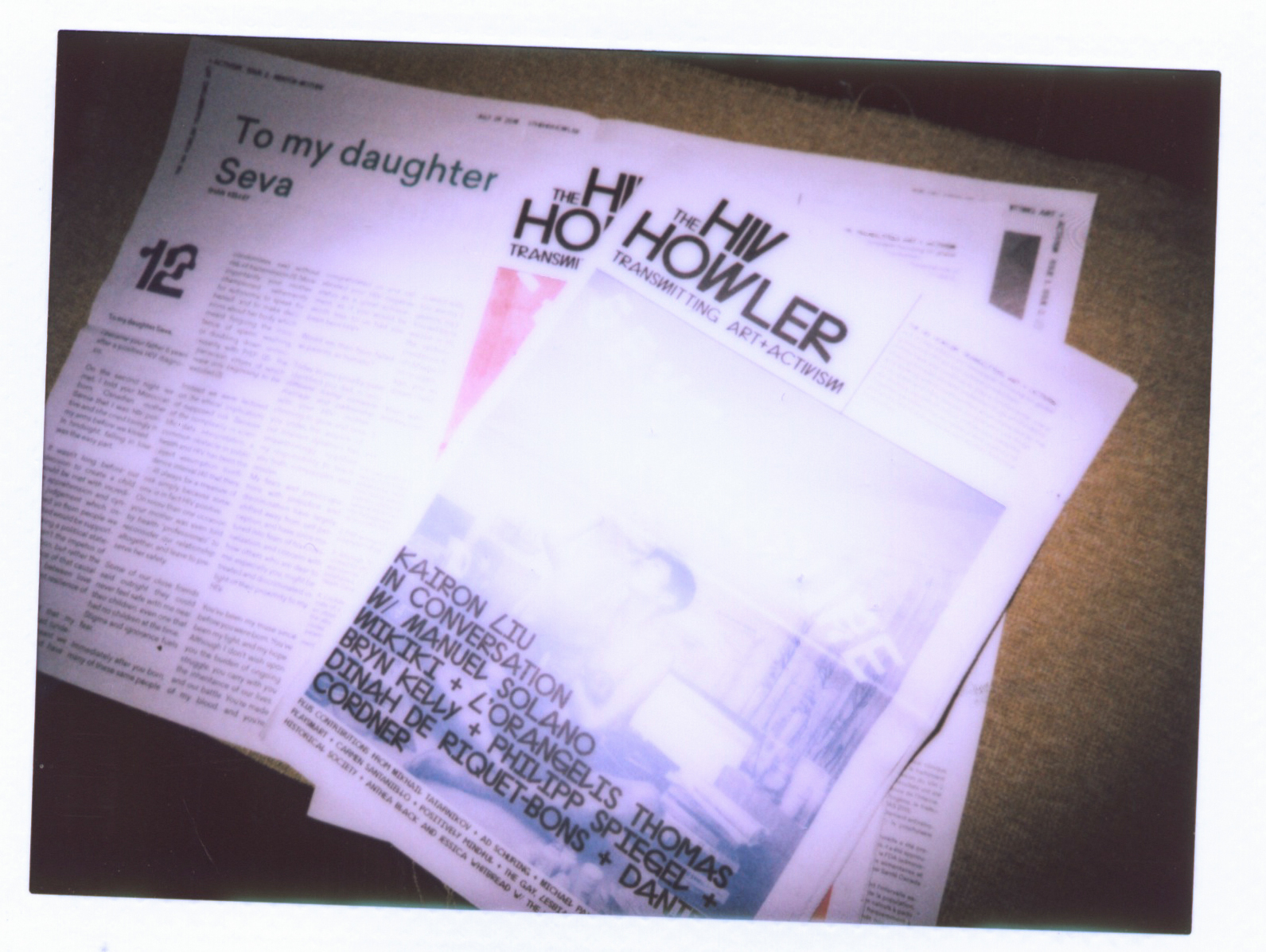

Since Humans as Hosts has begun, Kai has included the work in exhibitions in Taiwan and the US, experimenting with how to include the oral histories alongside the portraits. In Taiwan, if I understand correctly, the whole transcript, redacted to protect the subject and others, was available to be read. Additionally, quotes were pulled out and displayed at a table, where visitors could respond. In the US, Kai has created folders, almost like medical files, in which excerpts from the oral history are collected along with images from the portraits.

In both exhibition methods, viewers are being provided

multiple ways to know and learn about the person and their relationship with

HIV. And in both displays, there is not an attempt to privilege the visual over

the written word or vice versa. Instead, there is a belief that we need

multiple entry points to ever really begin to get a sense of a person and how

they might feel about any specific topic that impacts their lives. Humans

as Hosts is a process of co-creating meaning when it comes to HIV, and

community, making both through the lens of positivity.

F.

At one point in the oral history I am asked questions about my commitment to HIV, my status, and my sex life. The first question is issued as a statement:

Yesterday, Kai asked Ted how you would care so much about AIDS work and AIDS fight.

And I respond, knowing that implicit to the question is,

why do you care, if you are HIV negative: People

assume that if you do AIDS work the way we do AIDS work that you must been

living with it.

Or you have certain connection about it.

Yeah and now I have certain connections, but yeah, I don’t have it. I’ve been tested just in case you’re wondering. We’re you wondering if I had been tested? You were? You thought maybe I just was ignorant about my status?

No. I can be the interviewer now? I can be the interviewer now? Okay. My question was have you ever think about how would you feel if you are HIV positive. Have you ever think about it before and after?

Yeah. Yeah, I think about it a lot all the time.

Okay. Has it ever changed?

Yeah. Honestly, there’s times in my life it doesn’t feel inevitable. Does that make sense?

No.

I don’t bottom ; I’m a top primarily. I’ve tried bottoming and so my risk of HIV …

Yes, really low.

Is lower.

Yeah.

When it comes to sex, I’m a bit of a control freak.

What does that mean?

It means that I don’t … It would be hard for me to get HIV at this point.

True. Are you on PrEP?

No, I’m not on prep and I don’t use condoms but I also don’t bottom so I’m at risk.

It’s so funny. Wait. Are you waiting the moment that you got HIV?

No, I’m not waiting for the moment. I think that’s a really good question.

G.

When it comes to life with HIV, there has been many

treatment advancements in the last 30+ years, making it so an HIV diagnosis is

no longer a death sentence, but can be a manageable chronic illness. Often

standing in the way of making that a reality though is stigma and

discrimination, that can be felt both from systems and people, but also from

within someone’s

own heart. It is so hard to not feel guilt and shame when living with HIV.

Public health is often rooted in making HIV+ people feel that they are solely

responsible for the crisis. This is not true.

In part, to help deal with the ongoing social, political

and spiritual crisis of HIV, some friends and I created, What Would an

HIV Doula Do?. We are a collective of people from across the HIV

response who see a doula as someone in community who holds space during times

of transitions and that HIV is a series of transitions that begin long before

someone may take an HIV test, and long after someone may go on AIDS meds,

regardless of their status. We understand that no one gets HIV alone, so no one

should have to deal with it alone, so we attempt to hold space in public,

holding institutions responsible for how they are representing HIV, or making

space for people to communicate about HIV on their own terms. We find there is

still a lot of power in even just naming HIV in public and making space for

people to integrate their life story into that of the virus. We hope through

representation, familiarity and diversity of voices, HIV becomes more inviting

to discuss, and less harmful.

In this way, I see WWHIVDD is similar to Humans

as Hosts. Both are about collective responses to HIV, using culture to

improve the life chances for people with HIV. And both aim to create community

so that people understand that HIV is not an individual problem, but a shared

global experience in which some people, often already marginalized, are further

burden by the epidemic, while others are allowed to distance themselves through

ignorance.

This

is something I thought about after Kai and I wrapped up the last oral history

session. It was afternoon and the sun had just begun to set, flooding the city

with light and a sense of time passing. My tiredness was being held at bay by

my gratitude at being witnessed and having a chance to witness someone else. As

I walked uptown, I was thinking about how Humans as Host , like

oral history itself, is as much about the narrator or the subject as it is

about the interviewer or the photographer. Having to deal with the burden of

HIV, including the isolation, stigma and discrimination, Kai is doing what he

has to do, making community, and forging ahead as host for grief, anger and

uncertainty to be shared.

H.

Is there anything … I feel like we should wrap up. How do you feel?

Yeah, we’re good.

Is there anything you wanted to say?

I love you.

I love you; no, but I mean it. I know you mean it too. Okay, should we do a hum before we stop?

Okay.

Okay.

Yes.

Okay, three, two, one.

Ahmmmm.

Ahmmmm.

Theodore (ted) Kerr

New York

October 2018

Theodore (ted) Kerr is a Canadian-born, Brooklyn-based writer, artist and organizer whose work focuses on HIV/AIDS, community and care. He is a founding member of What Would An HIV Doula Do? For more information: tedkerr.club