New York based artist Eric Rhein speaks about his two exhibits, Lifelines, which

have been on view in his home state of Kentucky.

Lifelines is an exhibition at two locations in Lexington: at Institute 193 through

July 27 th , and the Lexington’s 21c Museum Hotel, through the end of August.

Todd Lanier Lester, of the Luv ‘til it Hurts campaign, asked Eric about the

shows—and his current and ongoing concerns.

TL:

What is the significance of your showing your work in Kentucky?

ER:

First, I want to thank you for having this conversation with me. As it happens,

today is the last day of the part of the show that’s at Institute 193. While the

companion show at the 21c Museum Hotel runs through August, exhibitions are

fleeting and only those who are geographically near have the opportunity to see

them. So, via this conversation, it’s rewarding when my artwork and the history

embodied in it can contribute to the conversation around HIV and AIDS, beyond

the walls of those exhibitions.

TL:

But tell us: How is Kentucky a special place for you?

ER:

Presenting Lifelines in Kentucky has a particular resonance. My family roots are

in Kentucky, and a sense of heritage and lineage are important to me. My Uncle

Lige Clarke was a formative pioneer in the Gay Rights movement of the 1960’s

and 70’s. He and my mother grew up in Hindman: a tiny, rural town in

Kentucky’s Appalachian Mountains—yet he had the fortitude to help lead the

way to an expansion in gay identity through his activism, like helping to

organize the first picket for Gay Rights at the White House in 1965, and also

founding and editing the first national gay newspaper, Gay, with his partner Jack

Nichols, in 1969. I see my drive to include my HIV status in the context of my

artwork as being linked to my uncle’s activism.

TL:

How does your memory of your uncle tie in with your own growth?

ER:

My uncle had a spiritual core, cultivated through his studies of Yoga and eastern

philosophies, and his appreciation of the great American poet Walt

Whitman—in fact, he always traveled with a copy of Whitman’s book-length

poem, Leaves of Grass. My uncle’s legacy—a liberated vision of life as a gay

man—was passed to me through my encountering autobiographical books

which he wrote with his partner Jack Nichols. That was just when I was entering

puberty and finding myself. Their book about their relationship and activism, I

Have More Fun With You Than Anybody, continues to inspire me. Further, AIDS

activism—which has a spiritual aspect—has contributed to the evolution and

visibility of LGBTQ identity.

TL:

I’m quite taken with the title of the two shows: Lifelines. Where does this title

come from?

ER:

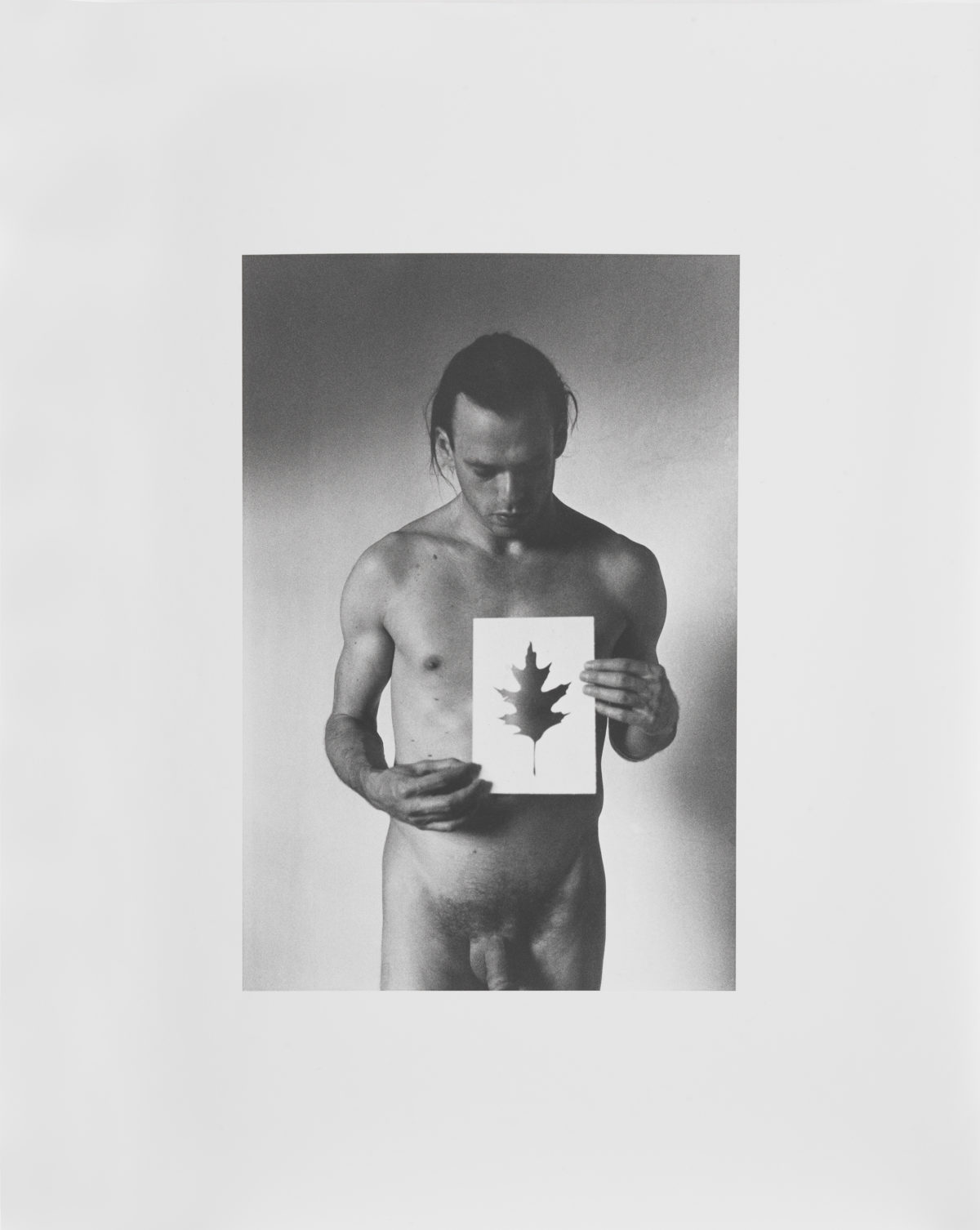

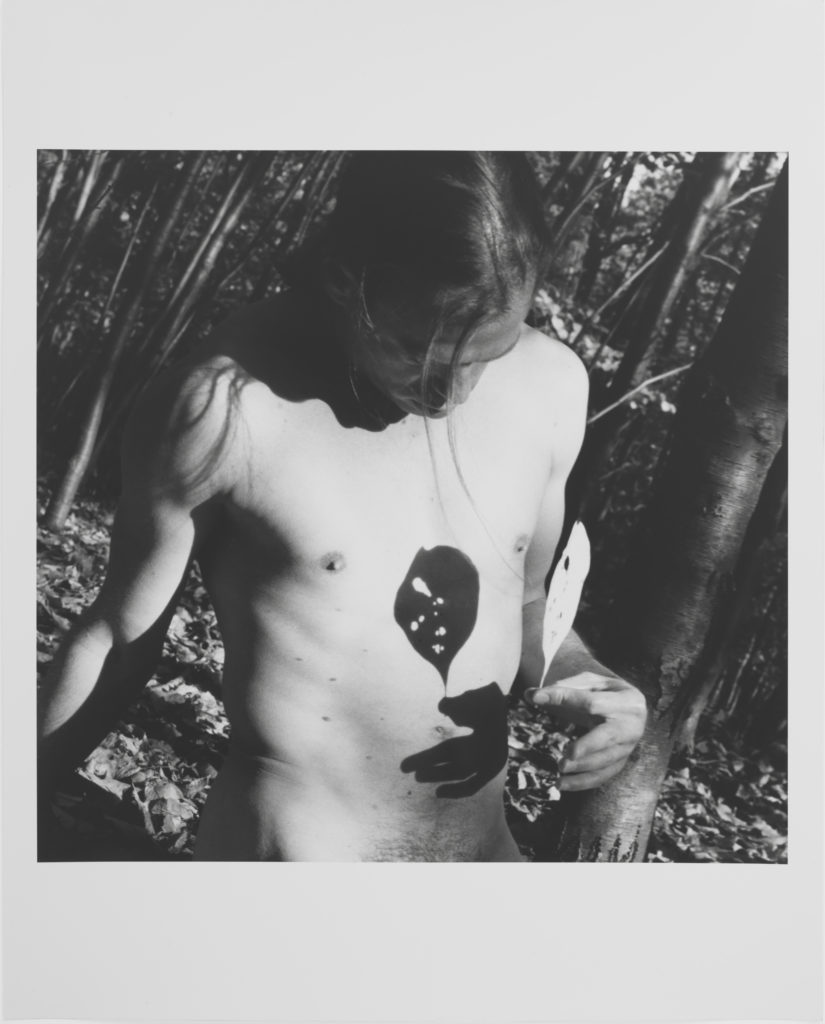

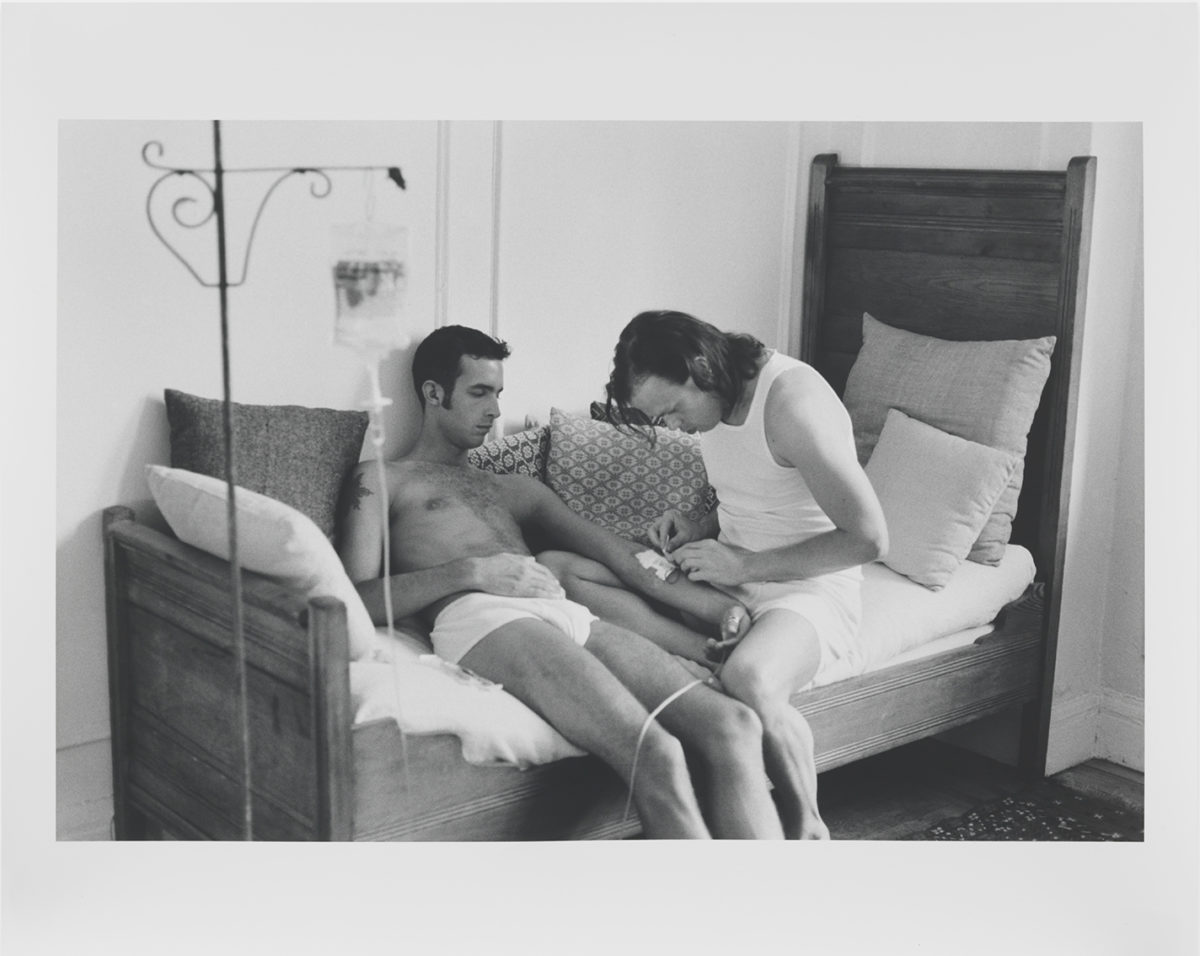

In the Institute 193 show is a series of three photos that I call Me with Ken. A

photo, from that series, is titled Lifeline. So the name of the overall exhibit

comes from that—yet reaches beyond to encompass themes running

throughout my work and my purpose for showing it. In that Me with Ken series

(which is from 1996) I’m pictured with my then boyfriend Ken, and it was

during the summer that protease inhibitors were initially released. Due to my

having been on those new medications, as part of a study, I was rapidly gaining

a renewed vitality. Ken hadn’t yet accessed the protease inhibitors, and was on

daily IV drips for declining health. Hence “lifelines” refers to this, and to a larger

interconnectedness as well. The intimacy and tenderness, heightened within

that period of shared vulnerability and mutual-caring, is shown in that series of

photos—and is something that I hope runs through my body of work, from my

photographs –to my AIDS Memorial Leaves.

TL:

I know that your project, Leaves, is an important part of your body of work. Can

you tell us about it?

ER:

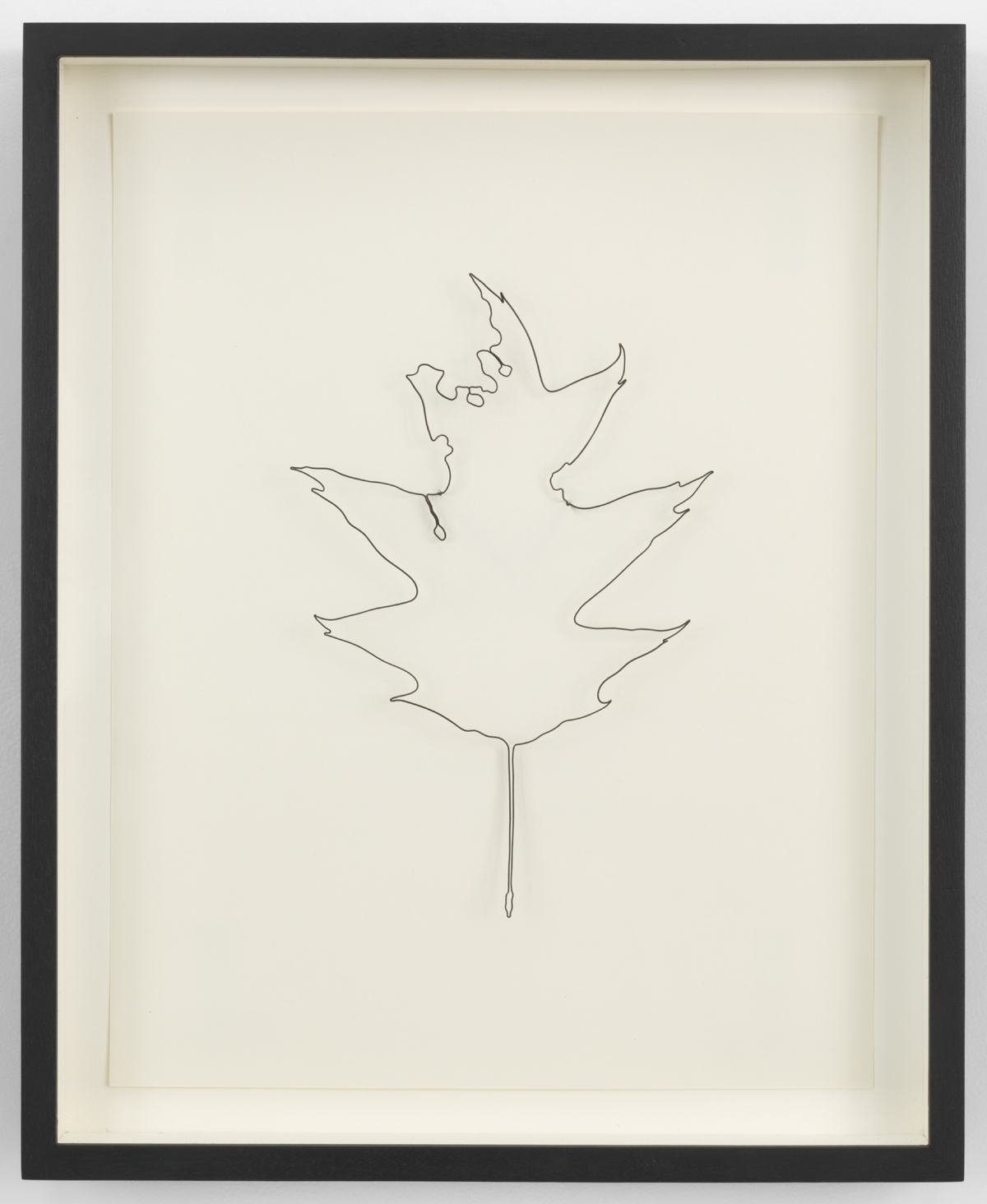

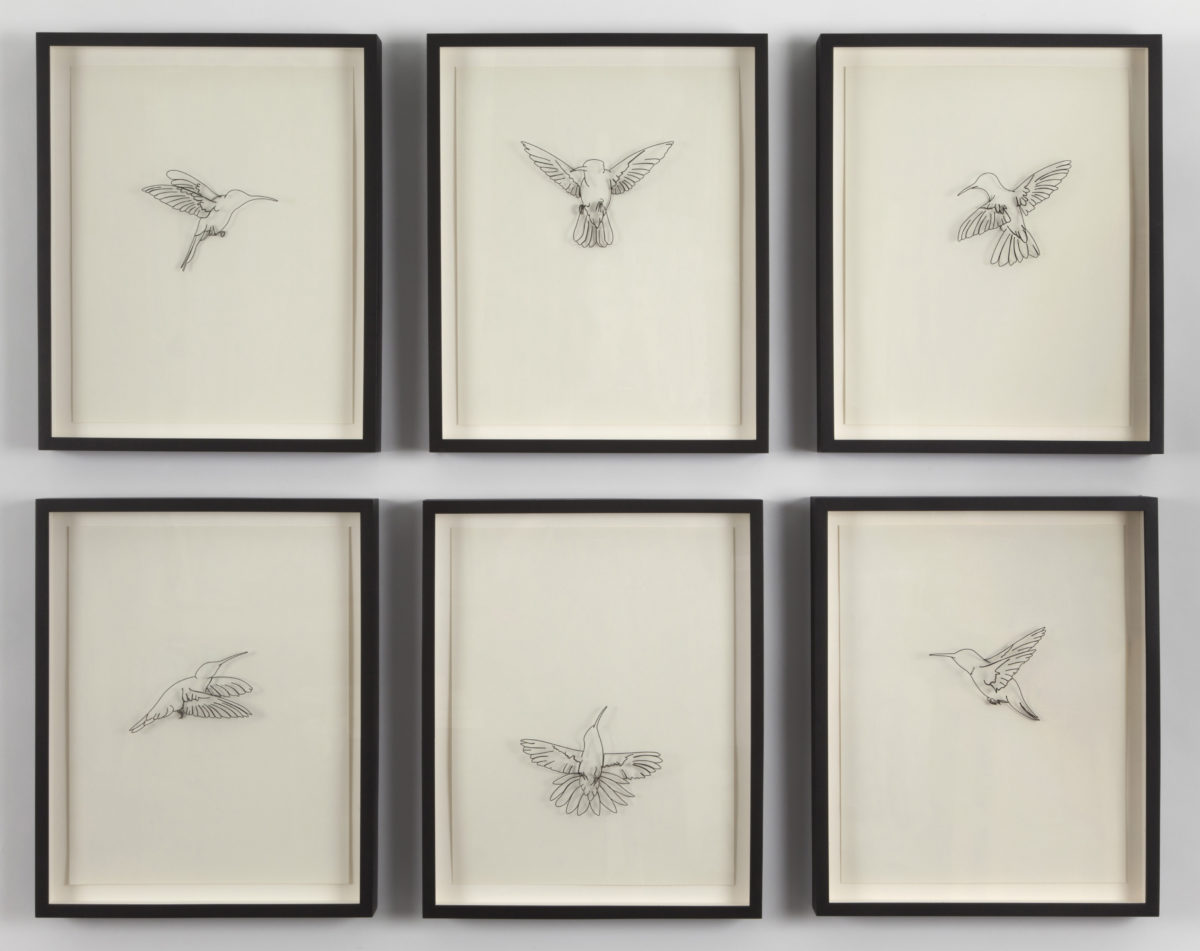

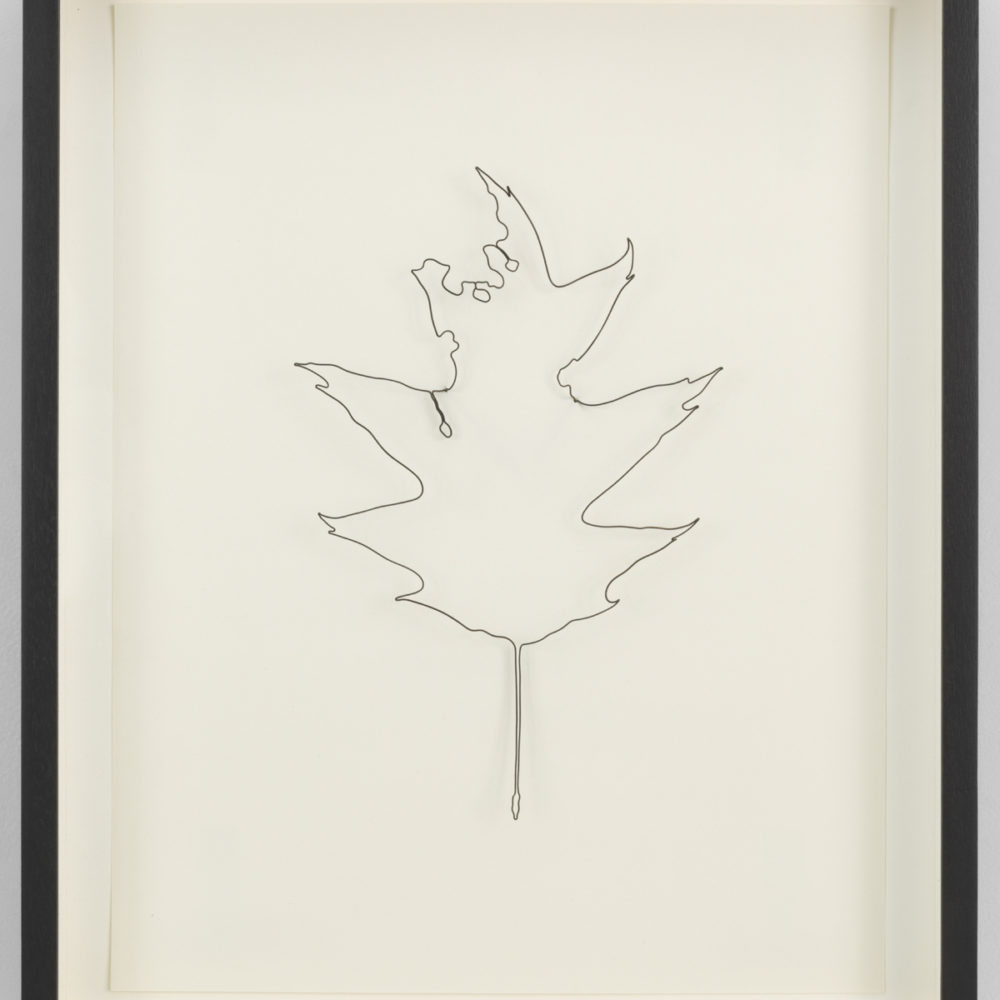

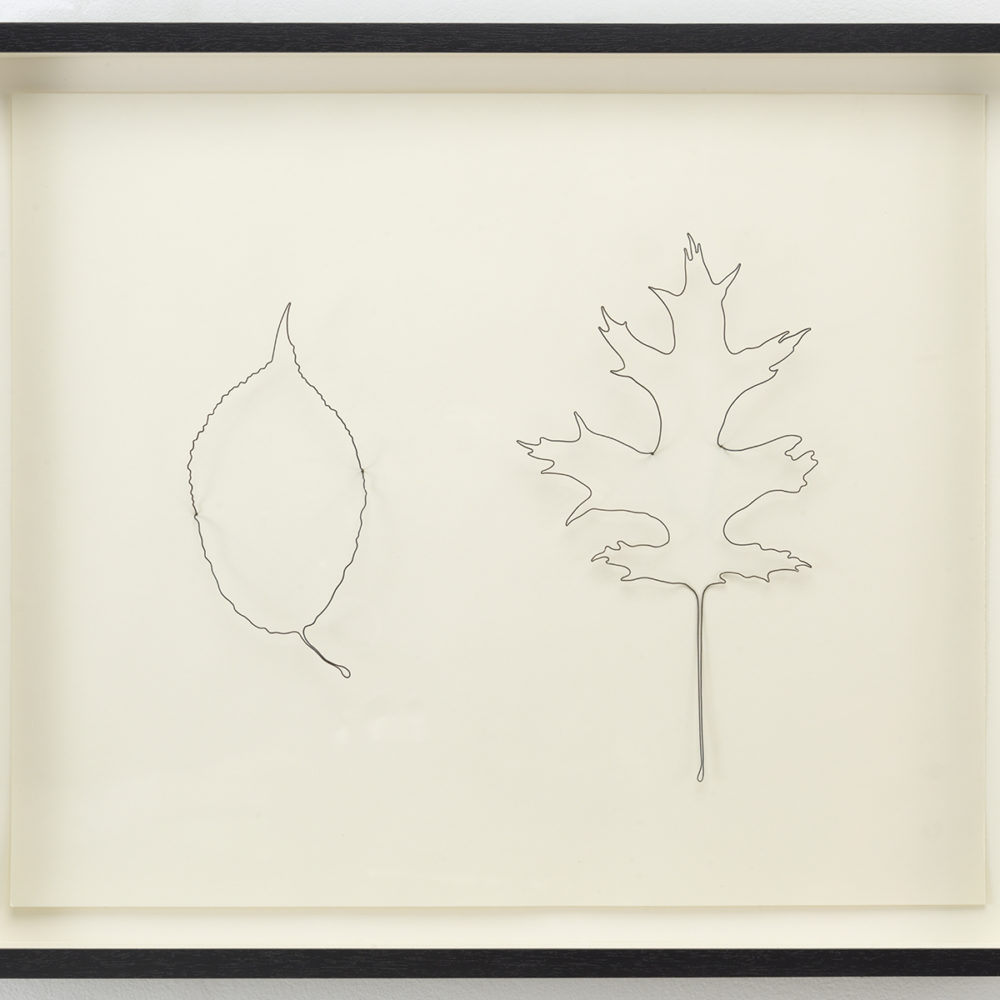

Leaves is an ongoing project which is a growing memorial to those I personally

knew who died of complications from AIDS. For each individual (and sometimes

for couples), I express my sense of them through a wire outline of a leaf.

Lifelines also points to an intergenerational exchange that is important to me.

When Paul Brown, the director of Institute 193 first came to my studio, two

years ago, it came out that he was about to turn 27, the same age I was when I

tested HIV positive in 1987. He had gravitated to my portfolio of photographs

depicted me and my companions in the 1990’s, sighting that they affirmed an

intimacy during the height of the AIDS epidemic, which contradicted the

narrative he’d been given when he first came out. Paul shared that his coming

out, like many men of his generation, was colored by associating being gay with

HIV—and, consequently, fear of sexual expression. Shifting the narrative he’d

inherited to a more expanded one, was primary to our working together.

TL:

Can you say a bit more about the relation of HIV to your artwork and life?

ER:

Having lived with HIV for just over three decades, I’ve found that there’s a real

potential for transcendence—yes, even within this complex history of

vulnerability, loss, and survival (and, maybe, sometimes, because of it.) Sharing

my artwork, which came through my experience of HIV and AIDS—and sharing

it with younger generations—brings a sense of purpose and healing.

TL:

I hear that you have written a piece that corresponds with many of the themes

you’ve explored in your artwork (and which we just talked about). Can you tell

me more? Will we have access to it soon?

ER:

Yes, “The Gathering” is a piece that I’m happy to share with the Luv ‘til it Hurts

community—and I’m glad to send it along soon, to be available on the website.

TL:

One more thing: is it true that there’s a book coming out on your work?

ER:

Yes. It too will be titled Lifelines—and will come out early next year.

= = = = = = =

Lifelines, an exhibit of Eric Rhein’s work, continues at the 2c Museum Hotel

through the end of August, 2019.

21c Museum Hotel

127 West Main Street

Lexington, Kentucky 40507

https://www.21cmuseumhotels.com/museum/exhibit/eric-rhein-lifelines/

Eric’s website is: http://www.ericrhein.com

= = = = = = = =