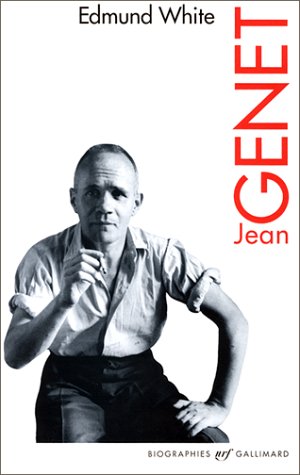

Feasting with Panthers (and Palestine): Edmund White’s Jean Genet #LPW2020

If writing is a committed utopian action, then the Jean Genet of Edmund White’s engaging, impressive, transformative Genet: A Biography was the epitome of manic depression. Genet wrote his five novels in five years, from 1942-47. After seven years of sadness and silence, he wrote his three best known plays in two years. The subsequent 1960’s were filled with death as his lover, Abdallah (a high wire performer) committed suicide, his agent and English translator Bernard Fruchtman committed suicide, and Genet himself tried to commit suicide. Then he entered into the other utopian endeavor: activism. From 1970 until his death in 1986, Genet was aligned with oppressed people and supported them in energetic ways, on their terms and on his own. White calls him “an apostle of the wretched of the earth.”

White’s use of the word “apostle” is, of course, an open invitation to question it. Apostles believe that the mortals they adore are not mortal. And, in that way, they err. Sartre, who, White points out, was an atheist, called his homage Saint Genet, so there was an ironic anti-religiosity to the book. But Genet was a man for whom adoration was deification; he described lovers as Gods. Genet’s love was possible, encompassing, invigorating – and annihilating. And since many people can only love in one way, one could assume that he might emotionally connect with oppressed people in the same manner that he loved his Nazi soldier lover/apparition turned underdog when left behind in liberated Paris in the novel Pompes Funebres.

Edmund White, if his life’s works are an indication, has loved far more rationally than Genet. He has been torn open, sure, and been impulsive and been destructive- i.e. human – but he has also been sensible, reasonable and accepting. His books are often a process of coming to terms. I would not use the world “apostle” to describe Edmund White as a lover, yet the concept of the “wretched of the earth” does unite the two. When White co-founded Gay Men’s Health Crisis in 1982, he got up from the typewriter on behalf of a despised group of people with no rights who were abandoned by their families and societies. They were living in illegality and were facing a terminal disease for which there was no epidemiological information, no treatment, and no cure. White – who has himself been openly HIV positive for decades – was one of them. Genet, on the other hand, died in 1986 at the beginning of the AIDS crisis. Although he had been poor, outcast and incarcerated, he was never, for example, Palestinian. There are universes of difference between the conditions of people with AIDS and Palestinians – though when I began to become a conscious and active worker for Palestine, I did notice some resonances. In both cases these were categories of people who were profoundly oppressed, who were treated with brutal abandonment and indifference, who were falsely cast as dangerous when they were in fact endangered, and who were treated like predators when they were the ones being attacked. In my carefully considered estimation, both people with AIDS and Palestinians have been lied about, pathologized, and inhumanely discarded. If a despised gay man, who had spent his life unjustly blamed when he hadn’t done anything wrong, truly understood his own condition he could – perhaps should – relate to Palestinians. That would, to me, be a rational response to oppression. Unfortunately, history shows that oppressed people often identity more strongly with the element of their demographic that still connects to domination. Many white gay people aspire to the unjustified powers of whiteness. Many male homosexuals rue any obstacle to male supremacy. When we are debased by ruthless ambition, we look up longingly towards the corruption of domination as we wish better for ourselves.

Born in 1910, Genet had already been arrested 8 times by the age of 17 for running away, for taking trains for free, for embezzling money to go to a carnival, and for stealing pens and notebooks. He was sentenced to two years at an agricultural prison for juveniles. White tells us that in order to get out of Mettray (a place that looms large in his work), Genet joined the army and was promoted to corporal. He then “volunteers” specifically for duty in the eastern part of the Mediterranean known as the Levant. In other words, at the age 19, he chose to be in an Arab place – in this case Syria. So the Arab world offered him an escape from the pain of France. The Arab world is to the young and French Jean Genet what France becomes to the young and American Edmund White: a place of permission. And permission is a kind of romance. It’s a rhapsody of relief, indulgence, and light-headed elevation. Of course, Genet’s arriving as a French soldier gave him a different source to his permission than Edmund White who not only loves men, but also graceful stylish beautiful things, sophisticated ways, and elevated traditions. Genet also found in the Levant male beauty, ancient cultures and intoxicating aesthetics, but his permission to do so came with the power of the French state. He had a uniform, a gun, a rank, and an historically imposed social role. The marginalized, despised, punished and alienated Genet came to his place of peace as a colonial. White had only the willingness to be reconstructed as a Francophile.

White describes Genet’s commitments to Palestine and to the Black Panthers as support for the “homeless,” and, it could be argued, both African Americans and Palestinians are living in exile, diasporic displacement, and elaborate fantasies of resolution and repair. Even Edward Said understood Genet’s pro-Palestinian position as the identification of one oppressed person with another. “Genet made the step, crossed the legal borders, that very few white men or women even attempted,” Said has written. “He traversed the space from the metropolitan center to the colony; his unquestioned solidarity was with the very same oppressed identified and so passionately analyzed, by [Frantz]Fanon,” Said continued, referring to the Afro-Caribbean psychiatrist, philosopher and revolutionary concerned with the psychopathology of colonization. And while it is easy and truthful to say that Genet also was homeless, in the most intimate sense of the word, unlike Palestinians, he did have a nation state, a passport and la langue natale which allowed him to be a writer with readers who also have passports, nation states and their own indigenous language.

White writes of Genet’s perspective of himself as an exception in the eyes of the various Arab communities he was sent to occupy. Of course, we don’t know what the Syrians actually thought of him, but we do learn that he felt they saw his difference in a positive light. Like Genet, I also see myself as a “friend of Palestine” and yet I do understand that that has nothing to do with whether or not individual Palestinians like me. Political relationships of solidarity are rife with the problem of supremacy, no matter how alienated or excluded the dominant party feels from their own societies. And it is easy to project one’s own enthusiasm of connection onto the less powerful partner. White wisely acknowledges this by pointing out that one of Genet’s favorite fantasy tropes is that of the benevolent/enamored cop, or complicit soldier, transgressing the rules of punishment because he is so moved by a vulnerable – and fictionalized – Genet.

At the age of 21, Genet re-enlisted, this time volunteering to go to Morocco. In 1934, at 23 and out of the army for only six months, he signed up for a third tour of duty, this time volunteering for Algeria. In 1936, for reasons I do not understand, he did not show up for roll call and deserted. He falsified his passport with the name Gejietti, was arrested in Albania. Then arrested in Yugoslavia. Then arrested in Vienna. Then arrested in Czechoslovakia, where he asked for political asylum. Despite some kind of asylum, he fled again and was arrested in Poland before crossing over into Nazi Germany. (Nazis were never a problem for Genet.) He got to Paris and was yet again arrested, this time in a department store for stealing twelve handkerchiefs. Over the next two years, he was arrested and incarcerated for desertion, expelled from the army, arrested for more free train riding, for stealing bottles of aperitifs, for carrying a gun, for stealing a shirt, for vagrancy, and for stealing a piece of silk. At the age of 30, he spent ten months in prison for stealing a suitcase and wallet, then anotehr four months for stealing history and philosophy books. He worked as a book-seller on the Seine, where he met readers, writers and intellectuals. Then he was arrested in front of Notre Dame and sentenced to three months for stealing a volume of Proust. In prison, at the age of 31, he started writing his first novel. Notre Dames des Fleurs. Two former customers, one of whom was a right-wing editor, introduced him to Jean Cocteau, who helped him immeasurably. Arrested again for stealing a rare edition of Verlaine, he was then eligible for life imprisonment but Cocteau argued in court that Genet was “the greatest writer of the modern era” and thus he was sentenced instead to 3 months, during which he wrote Miracle de la Rose. Three weeks after being freed, he stole more books and was jailed for four more months.

It’s a manic cycle, and most obviously filled with repetition and pervasive disregard for the obvious consequences of actions that might have alternatives. In this place and this time, Genet was a man who could not solve problems, unless his goal was to remain in prison. Certainly the meeting with Cocteau was lucky, but even luckier was the fact that Cocteau helped him at all – and to the extent that he did. I have to disclaim here that Edmund White himself helped me by reviewing my lesbian erotic, formally complex, 1994 novel Rat Bohemia in The New York Times and, thereb, elevating me with his accomplishments in the tradition of Cocteau’s helping Genet. But, I assure you, that most people with real power in literature do not help people who cannot help them back. That Cocteau, himself the homosexual author of Les Enfants Terribles (about a love affair between a brother and sister), understood Genet’s talents and bothered to make the effort is just a fluke of literary history. Lucky, lucky Saint Genet.

It was now 1943 and France was in the midst of its Nazi occupation. French people – especially Jews among them – were being deported to concentration camps in Poland and exterminated. Genet found himself held in Camp des Tourelles, a deportation cite. He was visited by Marc Barbezat, the powerful publisher of the magazine L’Arbalete who, with other powerful people, got Genet released. n I have no idea what role this publisher or Cocteau or any of Genet’s other powerful supporters played in interfering with the deportation of Jews. Cocteau did flirt with the German power elite, and other artists like Max Jacobs and Robert Desnos were deported and exterminated for being anti-Nazi or Jewish. Genet’s friends were not deported and continued to publish during the occupation. So, despite his homosexuality, his desertion, his endless incarcerations for crimes petty and pathetic, this homeless man’s life was saved in a period in which thousands of citizens of far greater social standing were sent off to be murdered because they were Jews, communists and Nazi resisters. I would like to know more about this and to understand more about Genet’s feelings about Jews, French anti-Semitism and the European Holocaust. Sartre claimed Genet to be an anti-semite, but understood it as a revulsion of other oppressed people. White quotes Sartre: “Since Genet wants his lovers to be executioners, he should never be sodomized by a victim. What repels Genet about Israelites is that he finds himself in their situations.” But actually, no, he was excused from their situation. So, given that he had more power than Jews, just as he had more power than Arabs, there is a contradiction in the theory of Genet as pro-Palestinian because he identified with the oppressed.

In 1944, still under Nazi occupation, Genet’s first novel, Notre Dame des Fleurs appeared in except in L’Arbalete. He met Sartre, also still in France, at Café Flore, which was still open despite the Nazi seizure of resources and severe rationing. And Genet’s lover, Jean DeCarnin died on the Communist barricades fighting to liberate Paris. Strange juxtaposition of events: one dies, the other drinks coffee. From then on, most of Genet’s important love relationships were to be with Arab men. The Nazis were defeated in 1945 and three years later Sartre and Cocteau petition for amnesty for Genet. In 1951, Gallimard published the complete works of Genet. All his books were banned in America until Grove Press broke the ban in 1963. This was another good reason for Edmund White, future author of explicitly gay literature, to have been enamored with France. It offered him a legacy of freedom.

But there is such a strange imbalance of values in all of this. A France brutally colonizing the Arab and African world – and deeply complicit with the deportation of Jews – listens to its own intellectuals and frees, publishes and awards its own homosexual experimental writer ex-convict. Then again, perhaps the things that made white homosexual men intolerable to American culture – principally the refusal to build families and reproduce – didn’t really matter that much to the French. Overt empires reproduce in their own brutal ways, and histories such as Adam Hochschild’s King Leopold’s Ghost, which is about the colonization of the Congo by Belgium, depict colonial culture as a homoerotic, homosocial and, in many cases, homosexual refuge. It is similar perhaps to our own genocidal westward expansion and cowboy culture.

In 1970, Genet was arrested with Marguerite Duras at a demonstration protesting the death of four African immigrant workers. As a Frenchman, he had often traveled in Africa, especially in French colonized countries. Yet he had little contact with African Americans outside of James Baldwin who was in sexual and racial exile in France. But once he surfaced as an activist, Genet was contacted by Black Panthers Connie Mathews and Michael Persitz to speak out on the jailing and government murders of much of their leadership. How the Panthers made the decision to ask him for help is unclear. A lot has been written about the macho nature of the Panther party, and much of that has also been softened, retrospectively. Huey P Newton, party chairman, famously said, “The homosexual may be the most revolutionary,” which is certainly very far from the white left, busy yelling “Pull her off the stage and fuck her,” when Marilyn Webb of Women’s Liberation tried to talk feminism at an anti-war rally that same year. Certainly the handsome Panther, Chairman Huey P Newton, and the stylish rank and file were a lot sexier than white leftists whose torn, baggy jeans and flannel shirts de-sexualized working class clothing, which would soon be tightened and re-masculinized by gay clone culture. Wanting to help the Panthers, Genet was denied a visa by the US because of his homosexuality, and so crossed the border illegally from Canada. For two months, he traveled the country, giving many public talks at universities and to the press on behalf of the Panthers. His many American adventures included a cocktail party at Stanford’s French department where he compared the Panthers to the Marquis de Sade due to their shared authenticity. He had a crush on Panther leader David Hilliard. Jane Fonda proposed doing a film with Genet. And one night he danced for some Panthers in a pink negligee. He may have been a Marxist, but he was still camp. The Panthers gave him a black leather jacket. He met 26-year-old UCLA Philosophy professor Angela Davis, who was a fluent French speaker from a family of learned French speakers. On May 1, he spoke to 25,000 people in New Haven and his speech was published by the Black Panther Party. He then hastily departed America when contacted by the Office of Immigration. Back in Europe, he published a defense of Angela Davis, who was now on FBI Wanted posters, named “Public Enemy Number One.” When she was arrested, he agreed for the first time to go on television where he delivered a talk “Angela Davis Is At Your Mercy.” In Prisoner of Love Genet reflected that “The Panthers symbolism was too easily deciphered to last. It was accepted quickly, but rejected because it was too easily understood.”

As the Panthers fractured, Genet became friends back in France with Mahmoud El Hamchari, the Paris representative of the Palestine Liberation Organization. His wife told Edmund White that Genet would come to their house unannounced and have long talks with El Hamchari about the divisions and corruption within the Panthers. So, as one political partner crumbled, another was born. White writes, “After following events in Jordan that proved disastrous for Palestinians, known as ‘Black September,’” Genet “accepted an invitation” to visit Palestinian refugee camps for one week. He stayed for six months and returned four times over the next two years. In November, 1970, he met Yasser Arafat for less than thirty minutes. But Arafat did give Genet a pass permitting free travel in any PLO territory and asked him to write a book about Palestinians, which Genet completed fifteen years later. White writes that Genet “preferred to think that the Arab world should be Palestinized rather than the Palestinian revolution should be Arabized. To Genet the only positive vision of the future should be socialist, not theological: his analysis of the failure of Zionism was that it had begun as a socialist experiment but had degenerated quickly into a theological state.”

Just as in Syria, there is not much information about how the Palestinians experienced Genet, most of the information coming from Genet’s version of the relationship. As in Syria, he described himself as well-liked. Genet says that he shocked Palestinians by telling them he was homosexual and an atheist, “an avowal that made them burst out laughing,” he claimed. But who knows what really happened. I am fascinated by Genet’s “invitations.” As an openly lesbian woman who is a “friend of Palestine,” I wonder if Genet was the first out queer in political solidarity with Palestinians, as opposed to colonials whose only investments were a sexual interest in Arab men.

The visit took place after the 1967 Six-Day War, and much of the world was troubled by the Israeli occupation of more territory and the creation of yet more refugees on top of the people still in exile from their expulsion by the founding of the Israeli state in 1948. Although Palestine is and was a “place”, the specific geographical boundaries of this “home” were different in people’s minds than in legal realities. In fact, “Palestine” was now The West Bank, Gaza, the Golan Heights, refugee camps in Jordan and in Lebanon and in Syria, as well as a global diaspora of refugees from Kuwait to London to Detroit. “Palestine” was also the memories, the still-standing houses now lived in by Israelis, and the land, sea and hills that many Palestinians would never see again. His visits stimulated a series of articles and petitions and participations with Michel Foucault on anti-prison work and with Gilles Deleuze in support of Arab workers in France, as well as the rights of North African immigrants.

At the age of 64, Genet met his last lover, Mohammed El Katranai, in Tangiers. They lived together in a small apartment in the Saint Denis suburb of Paris. At the age of 72, suffering from throat cancer, Genet moved to Morocco. From this base, he traveled to Lebanon with Leila Shahid, a young Palestinian activist. In September, 1982, Genet was in Beirut when Israelis invaded. This assault enabled Christian militias to massacre Palestinians in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps where Palestinians are still living in 2017.. Jim Hubbard and I visited Sabra with Lebanese queer activist Lynne Darwich in 2013. Genet was one of the first outsiders to enter Shatila on September 19, 1982, and found the place strewn with corpses. He wrote “Four Hours at Shatila,” which was published in The Journal of Palestinian Studies. I don’t know if he chose this venue to support the journal, or if the piece had been rejected by more widely-read and mainstream publications. Returning to Morocco, he started to write Prisoner of Love, based in fifteen years of notes about the Black Panther and Palestinian experiences. On April 15, 1986 he died of cancer at the age of 76. He was buried in Larache, Morocco. Prisoner of Love was published one month later.

If Genet ever had a “home,” it was in the Arab world, a world he first entered as a colonial soldier. It was as a colonial soldier that Genet had his first experience of authority, group belonging, sway. It was in the Arab world that he found lovers, often younger, poorer, with less social currency. It was Palestine that “invited” him, while America refused his request for a visa. American homosexuals now have, what Rutgers Professor Jasbir Puar has named “Homonationalism,” i.e. those of us who are white and male, who marry and reproduce, who are documented, who are not incarcerated, who have homes and who support the military and US imperial wars, are now invited to identify with the American, Canadian, British, German, French, Dutch, and Israeli state apparatus of punishment and enforcement. Despite being a homosexual convict, Genet experienced this same elevation by being a French soldier. But the status of Palestinians has not changed since Genet walked into Shatila and witnessed murdered civilians lying on its grounds in 1982. Palestinians are still mass murdered; they are still denied a “home.” There are still questions for us to grapple with regarding Jean Genet. Was his support for Palestine – which was unusual, energetic, sincere, effortful and significant – rooted in the identification of one homeless person with another, one marginalized, unjustly punished person with another? Was it, simultaneously, a relationship of a French person to an Arab one, a Frenchman whose only place of supremacy in his own cultural framework was in relationship to the Arabs he could love and to whom he could make a difference? Or was he attracted to the Palestinians and the Black Panthers who needed “Jean Genet”?