Feasting with Panthers (and Palestine): Edmund White’s Jean Genet #LPW2020

If writing is a committed utopian action, then the Jean Genet of Edmund White’s engaging, impressive, transformative Genet: A Biography was the epitome of manic depression. Genet wrote his five novels in five years, from 1942-47. After seven years of sadness and silence, he wrote his three best known plays in two years. The subsequent 1960’s were filled with death as his lover, Abdallah (a high wire performer) committed suicide, his agent and English translator Bernard Fruchtman committed suicide, and Genet himself tried to commit suicide. Then he entered into the other utopian endeavor: activism. From 1970 until his death in 1986, Genet was aligned with oppressed people and supported them in energetic ways, on their terms and on his own. White calls him “an apostle of the wretched of the earth.”

White’s use of the word “apostle” is, of course, an open invitation to question it. Apostles believe that the mortals they adore are not mortal. And, in that way, they err. Sartre, who, White points out, was an atheist, called his homage Saint Genet, so there was an ironic anti-religiosity to the book. But Genet was a man for whom adoration was deification; he described lovers as Gods. Genet’s love was possible, encompassing, invigorating – and annihilating. And since many people can only love in one way, one could assume that he might emotionally connect with oppressed people in the same manner that he loved his Nazi soldier lover/apparition turned underdog when left behind in liberated Paris in the novel Pompes Funebres.

Edmund White, if his life’s works are an indication, has loved far more rationally than Genet. He has been torn open, sure, and been impulsive and been destructive- i.e. human – but he has also been sensible, reasonable and accepting. His books are often a process of coming to terms. I would not use the world “apostle” to describe Edmund White as a lover, yet the concept of the “wretched of the earth” does unite the two. When White co-founded Gay Men’s Health Crisis in 1982, he got up from the typewriter on behalf of a despised group of people with no rights who were abandoned by their families and societies. They were living in illegality and were facing a terminal disease for which there was no epidemiological information, no treatment, and no cure. White – who has himself been openly HIV positive for decades – was one of them. Genet, on the other hand, died in 1986 at the beginning of the AIDS crisis. Although he had been poor, outcast and incarcerated, he was never, for example, Palestinian. There are universes of difference between the conditions of people with AIDS and Palestinians – though when I began to become a conscious and active worker for Palestine, I did notice some resonances. In both cases these were categories of people who were profoundly oppressed, who were treated with brutal abandonment and indifference, who were falsely cast as dangerous when they were in fact endangered, and who were treated like predators when they were the ones being attacked. In my carefully considered estimation, both people with AIDS and Palestinians have been lied about, pathologized, and inhumanely discarded. If a despised gay man, who had spent his life unjustly blamed when he hadn’t done anything wrong, truly understood his own condition he could – perhaps should – relate to Palestinians. That would, to me, be a rational response to oppression. Unfortunately, history shows that oppressed people often identity more strongly with the element of their demographic that still connects to domination. Many white gay people aspire to the unjustified powers of whiteness. Many male homosexuals rue any obstacle to male supremacy. When we are debased by ruthless ambition, we look up longingly towards the corruption of domination as we wish better for ourselves.

Born in 1910, Genet had already been arrested 8 times by the age of 17 for running away, for taking trains for free, for embezzling money to go to a carnival, and for stealing pens and notebooks. He was sentenced to two years at an agricultural prison for juveniles. White tells us that in order to get out of Mettray (a place that looms large in his work), Genet joined the army and was promoted to corporal. He then “volunteers” specifically for duty in the eastern part of the Mediterranean known as the Levant. In other words, at the age 19, he chose to be in an Arab place – in this case Syria. So the Arab world offered him an escape from the pain of France. The Arab world is to the young and French Jean Genet what France becomes to the young and American Edmund White: a place of permission. And permission is a kind of romance. It’s a rhapsody of relief, indulgence, and light-headed elevation. Of course, Genet’s arriving as a French soldier gave him a different source to his permission than Edmund White who not only loves men, but also graceful stylish beautiful things, sophisticated ways, and elevated traditions. Genet also found in the Levant male beauty, ancient cultures and intoxicating aesthetics, but his permission to do so came with the power of the French state. He had a uniform, a gun, a rank, and an historically imposed social role. The marginalized, despised, punished and alienated Genet came to his place of peace as a colonial. White had only the willingness to be reconstructed as a Francophile.

White describes Genet’s commitments to Palestine and to the Black Panthers as support for the “homeless,” and, it could be argued, both African Americans and Palestinians are living in exile, diasporic displacement, and elaborate fantasies of resolution and repair. Even Edward Said understood Genet’s pro-Palestinian position as the identification of one oppressed person with another. “Genet made the step, crossed the legal borders, that very few white men or women even attempted,” Said has written. “He traversed the space from the metropolitan center to the colony; his unquestioned solidarity was with the very same oppressed identified and so passionately analyzed, by [Frantz]Fanon,” Said continued, referring to the Afro-Caribbean psychiatrist, philosopher and revolutionary concerned with the psychopathology of colonization. And while it is easy and truthful to say that Genet also was homeless, in the most intimate sense of the word, unlike Palestinians, he did have a nation state, a passport and la langue natale which allowed him to be a writer with readers who also have passports, nation states and their own indigenous language.

White writes of Genet’s perspective of himself as an exception in the eyes of the various Arab communities he was sent to occupy. Of course, we don’t know what the Syrians actually thought of him, but we do learn that he felt they saw his difference in a positive light. Like Genet, I also see myself as a “friend of Palestine” and yet I do understand that that has nothing to do with whether or not individual Palestinians like me. Political relationships of solidarity are rife with the problem of supremacy, no matter how alienated or excluded the dominant party feels from their own societies. And it is easy to project one’s own enthusiasm of connection onto the less powerful partner. White wisely acknowledges this by pointing out that one of Genet’s favorite fantasy tropes is that of the benevolent/enamored cop, or complicit soldier, transgressing the rules of punishment because he is so moved by a vulnerable – and fictionalized – Genet.

At the age of 21, Genet re-enlisted, this time volunteering to go to Morocco. In 1934, at 23 and out of the army for only six months, he signed up for a third tour of duty, this time volunteering for Algeria. In 1936, for reasons I do not understand, he did not show up for roll call and deserted. He falsified his passport with the name Gejietti, was arrested in Albania. Then arrested in Yugoslavia. Then arrested in Vienna. Then arrested in Czechoslovakia, where he asked for political asylum. Despite some kind of asylum, he fled again and was arrested in Poland before crossing over into Nazi Germany. (Nazis were never a problem for Genet.) He got to Paris and was yet again arrested, this time in a department store for stealing twelve handkerchiefs. Over the next two years, he was arrested and incarcerated for desertion, expelled from the army, arrested for more free train riding, for stealing bottles of aperitifs, for carrying a gun, for stealing a shirt, for vagrancy, and for stealing a piece of silk. At the age of 30, he spent ten months in prison for stealing a suitcase and wallet, then anotehr four months for stealing history and philosophy books. He worked as a book-seller on the Seine, where he met readers, writers and intellectuals. Then he was arrested in front of Notre Dame and sentenced to three months for stealing a volume of Proust. In prison, at the age of 31, he started writing his first novel. Notre Dames des Fleurs. Two former customers, one of whom was a right-wing editor, introduced him to Jean Cocteau, who helped him immeasurably. Arrested again for stealing a rare edition of Verlaine, he was then eligible for life imprisonment but Cocteau argued in court that Genet was “the greatest writer of the modern era” and thus he was sentenced instead to 3 months, during which he wrote Miracle de la Rose. Three weeks after being freed, he stole more books and was jailed for four more months.

It’s a manic cycle, and most obviously filled with repetition and pervasive disregard for the obvious consequences of actions that might have alternatives. In this place and this time, Genet was a man who could not solve problems, unless his goal was to remain in prison. Certainly the meeting with Cocteau was lucky, but even luckier was the fact that Cocteau helped him at all – and to the extent that he did. I have to disclaim here that Edmund White himself helped me by reviewing my lesbian erotic, formally complex, 1994 novel Rat Bohemia in The New York Times and, thereb, elevating me with his accomplishments in the tradition of Cocteau’s helping Genet. But, I assure you, that most people with real power in literature do not help people who cannot help them back. That Cocteau, himself the homosexual author of Les Enfants Terribles (about a love affair between a brother and sister), understood Genet’s talents and bothered to make the effort is just a fluke of literary history. Lucky, lucky Saint Genet.

It was now 1943 and France was in the midst of its Nazi occupation. French people – especially Jews among them – were being deported to concentration camps in Poland and exterminated. Genet found himself held in Camp des Tourelles, a deportation cite. He was visited by Marc Barbezat, the powerful publisher of the magazine L’Arbalete who, with other powerful people, got Genet released. n I have no idea what role this publisher or Cocteau or any of Genet’s other powerful supporters played in interfering with the deportation of Jews. Cocteau did flirt with the German power elite, and other artists like Max Jacobs and Robert Desnos were deported and exterminated for being anti-Nazi or Jewish. Genet’s friends were not deported and continued to publish during the occupation. So, despite his homosexuality, his desertion, his endless incarcerations for crimes petty and pathetic, this homeless man’s life was saved in a period in which thousands of citizens of far greater social standing were sent off to be murdered because they were Jews, communists and Nazi resisters. I would like to know more about this and to understand more about Genet’s feelings about Jews, French anti-Semitism and the European Holocaust. Sartre claimed Genet to be an anti-semite, but understood it as a revulsion of other oppressed people. White quotes Sartre: “Since Genet wants his lovers to be executioners, he should never be sodomized by a victim. What repels Genet about Israelites is that he finds himself in their situations.” But actually, no, he was excused from their situation. So, given that he had more power than Jews, just as he had more power than Arabs, there is a contradiction in the theory of Genet as pro-Palestinian because he identified with the oppressed.

In 1944, still under Nazi occupation, Genet’s first novel, Notre Dame des Fleurs appeared in except in L’Arbalete. He met Sartre, also still in France, at Café Flore, which was still open despite the Nazi seizure of resources and severe rationing. And Genet’s lover, Jean DeCarnin died on the Communist barricades fighting to liberate Paris. Strange juxtaposition of events: one dies, the other drinks coffee. From then on, most of Genet’s important love relationships were to be with Arab men. The Nazis were defeated in 1945 and three years later Sartre and Cocteau petition for amnesty for Genet. In 1951, Gallimard published the complete works of Genet. All his books were banned in America until Grove Press broke the ban in 1963. This was another good reason for Edmund White, future author of explicitly gay literature, to have been enamored with France. It offered him a legacy of freedom.

But there is such a strange imbalance of values in all of this. A France brutally colonizing the Arab and African world – and deeply complicit with the deportation of Jews – listens to its own intellectuals and frees, publishes and awards its own homosexual experimental writer ex-convict. Then again, perhaps the things that made white homosexual men intolerable to American culture – principally the refusal to build families and reproduce – didn’t really matter that much to the French. Overt empires reproduce in their own brutal ways, and histories such as Adam Hochschild’s King Leopold’s Ghost, which is about the colonization of the Congo by Belgium, depict colonial culture as a homoerotic, homosocial and, in many cases, homosexual refuge. It is similar perhaps to our own genocidal westward expansion and cowboy culture.

In 1970, Genet was arrested with Marguerite Duras at a demonstration protesting the death of four African immigrant workers. As a Frenchman, he had often traveled in Africa, especially in French colonized countries. Yet he had little contact with African Americans outside of James Baldwin who was in sexual and racial exile in France. But once he surfaced as an activist, Genet was contacted by Black Panthers Connie Mathews and Michael Persitz to speak out on the jailing and government murders of much of their leadership. How the Panthers made the decision to ask him for help is unclear. A lot has been written about the macho nature of the Panther party, and much of that has also been softened, retrospectively. Huey P Newton, party chairman, famously said, “The homosexual may be the most revolutionary,” which is certainly very far from the white left, busy yelling “Pull her off the stage and fuck her,” when Marilyn Webb of Women’s Liberation tried to talk feminism at an anti-war rally that same year. Certainly the handsome Panther, Chairman Huey P Newton, and the stylish rank and file were a lot sexier than white leftists whose torn, baggy jeans and flannel shirts de-sexualized working class clothing, which would soon be tightened and re-masculinized by gay clone culture. Wanting to help the Panthers, Genet was denied a visa by the US because of his homosexuality, and so crossed the border illegally from Canada. For two months, he traveled the country, giving many public talks at universities and to the press on behalf of the Panthers. His many American adventures included a cocktail party at Stanford’s French department where he compared the Panthers to the Marquis de Sade due to their shared authenticity. He had a crush on Panther leader David Hilliard. Jane Fonda proposed doing a film with Genet. And one night he danced for some Panthers in a pink negligee. He may have been a Marxist, but he was still camp. The Panthers gave him a black leather jacket. He met 26-year-old UCLA Philosophy professor Angela Davis, who was a fluent French speaker from a family of learned French speakers. On May 1, he spoke to 25,000 people in New Haven and his speech was published by the Black Panther Party. He then hastily departed America when contacted by the Office of Immigration. Back in Europe, he published a defense of Angela Davis, who was now on FBI Wanted posters, named “Public Enemy Number One.” When she was arrested, he agreed for the first time to go on television where he delivered a talk “Angela Davis Is At Your Mercy.” In Prisoner of Love Genet reflected that “The Panthers symbolism was too easily deciphered to last. It was accepted quickly, but rejected because it was too easily understood.”

As the Panthers fractured, Genet became friends back in France with Mahmoud El Hamchari, the Paris representative of the Palestine Liberation Organization. His wife told Edmund White that Genet would come to their house unannounced and have long talks with El Hamchari about the divisions and corruption within the Panthers. So, as one political partner crumbled, another was born. White writes, “After following events in Jordan that proved disastrous for Palestinians, known as ‘Black September,’” Genet “accepted an invitation” to visit Palestinian refugee camps for one week. He stayed for six months and returned four times over the next two years. In November, 1970, he met Yasser Arafat for less than thirty minutes. But Arafat did give Genet a pass permitting free travel in any PLO territory and asked him to write a book about Palestinians, which Genet completed fifteen years later. White writes that Genet “preferred to think that the Arab world should be Palestinized rather than the Palestinian revolution should be Arabized. To Genet the only positive vision of the future should be socialist, not theological: his analysis of the failure of Zionism was that it had begun as a socialist experiment but had degenerated quickly into a theological state.”

Just as in Syria, there is not much information about how the Palestinians experienced Genet, most of the information coming from Genet’s version of the relationship. As in Syria, he described himself as well-liked. Genet says that he shocked Palestinians by telling them he was homosexual and an atheist, “an avowal that made them burst out laughing,” he claimed. But who knows what really happened. I am fascinated by Genet’s “invitations.” As an openly lesbian woman who is a “friend of Palestine,” I wonder if Genet was the first out queer in political solidarity with Palestinians, as opposed to colonials whose only investments were a sexual interest in Arab men.

The visit took place after the 1967 Six-Day War, and much of the world was troubled by the Israeli occupation of more territory and the creation of yet more refugees on top of the people still in exile from their expulsion by the founding of the Israeli state in 1948. Although Palestine is and was a “place”, the specific geographical boundaries of this “home” were different in people’s minds than in legal realities. In fact, “Palestine” was now The West Bank, Gaza, the Golan Heights, refugee camps in Jordan and in Lebanon and in Syria, as well as a global diaspora of refugees from Kuwait to London to Detroit. “Palestine” was also the memories, the still-standing houses now lived in by Israelis, and the land, sea and hills that many Palestinians would never see again. His visits stimulated a series of articles and petitions and participations with Michel Foucault on anti-prison work and with Gilles Deleuze in support of Arab workers in France, as well as the rights of North African immigrants.

At the age of 64, Genet met his last lover, Mohammed El Katranai, in Tangiers. They lived together in a small apartment in the Saint Denis suburb of Paris. At the age of 72, suffering from throat cancer, Genet moved to Morocco. From this base, he traveled to Lebanon with Leila Shahid, a young Palestinian activist. In September, 1982, Genet was in Beirut when Israelis invaded. This assault enabled Christian militias to massacre Palestinians in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps where Palestinians are still living in 2017.. Jim Hubbard and I visited Sabra with Lebanese queer activist Lynne Darwich in 2013. Genet was one of the first outsiders to enter Shatila on September 19, 1982, and found the place strewn with corpses. He wrote “Four Hours at Shatila,” which was published in The Journal of Palestinian Studies. I don’t know if he chose this venue to support the journal, or if the piece had been rejected by more widely-read and mainstream publications. Returning to Morocco, he started to write Prisoner of Love, based in fifteen years of notes about the Black Panther and Palestinian experiences. On April 15, 1986 he died of cancer at the age of 76. He was buried in Larache, Morocco. Prisoner of Love was published one month later.

If Genet ever had a “home,” it was in the Arab world, a world he first entered as a colonial soldier. It was as a colonial soldier that Genet had his first experience of authority, group belonging, sway. It was in the Arab world that he found lovers, often younger, poorer, with less social currency. It was Palestine that “invited” him, while America refused his request for a visa. American homosexuals now have, what Rutgers Professor Jasbir Puar has named “Homonationalism,” i.e. those of us who are white and male, who marry and reproduce, who are documented, who are not incarcerated, who have homes and who support the military and US imperial wars, are now invited to identify with the American, Canadian, British, German, French, Dutch, and Israeli state apparatus of punishment and enforcement. Despite being a homosexual convict, Genet experienced this same elevation by being a French soldier. But the status of Palestinians has not changed since Genet walked into Shatila and witnessed murdered civilians lying on its grounds in 1982. Palestinians are still mass murdered; they are still denied a “home.” There are still questions for us to grapple with regarding Jean Genet. Was his support for Palestine – which was unusual, energetic, sincere, effortful and significant – rooted in the identification of one homeless person with another, one marginalized, unjustly punished person with another? Was it, simultaneously, a relationship of a French person to an Arab one, a Frenchman whose only place of supremacy in his own cultural framework was in relationship to the Arabs he could love and to whom he could make a difference? Or was he attracted to the Palestinians and the Black Panthers who needed “Jean Genet”?

Love Positive Women in AR/PT/ES

[*It is very exciting (and an honor) to get to imagine and implement ideas for Love Positive Women 2020 in Khartoum (Sudan), New York City (US), São Paulo (Brasil) and other places in South America. Designer Adham Bakry (Port Said/Cairo) came up with a version of the Love Positive Women insignia in Arabic and Gustavo Marcasse in both Portuguese and Spanish. Love Positive Women is a project by Jessica Whitbread. xo Todd]

A series for LovePositiveWomen2020; #LPW2020, pre-C

Image: $oropositiva, by Micaela Cyrino for LovePositiveWomen2019

Collage on greaseproof paper and serigraphy

30 x 40cm

In some ways the whole LUV experience has geared us up for Love Positive Women 2020. In March 2019 I visited Egypt and afterwards, Paris where I met the Ankh (Arab Network for Knowledge on Human Rights) Association. The Ankh guys moved to Paris after a long period of activism on access to HIV meds in Cairo. From Paris they made the Points of Life exhibit that featured artists and activists from Egypt and the Middle East living with HIV. ‘Behind the Curtain’ is an image and text by Iman, an artist living in Egypt. Daniel Santiago Salguero’s project, Luciérnagas began with the idea to consider the changing situation–HIV info, support and medication access–in Bogotá with new arrivals of Venezuelans in the wake of that country’s financial crisis. It ended as an experimental performance in Bogotá’s Botanical Gardens. I met Jackie during the project’s conclusion in October 2019. Daniel interviews her for LovePositiveWomen2020 and further reflects on the Luciérnagas process.

On a previous project I met the Nhimbe Trust based in Bulawayo (Zimbabwe), and its founder, Joshua Nyapimbi. Originally there was meant to be an event there at their offices during LPW2020, but due to a roof collapse this is not possible. A women’s HIV support group, CHOOSE LIFE meets at Nhimbe Trust and developed a play, MAIDEI to highlight local issues pertaining to HIV care and treatment. CHOOSE LIFE recognizes that there are resources already available in Gokwe South (District where Bulawayo is located), but positive women do not have full access to these yet. The Nhimbe Trust and CHOOSE LIFE offered the script of MAIDEI to be serialized throughout LPW2020 in six installments. I interviewed Joshua on the history of the piece, and he explained that “the play has been used extensively, initially created with a rural-based support group for HIV positive women who acted in the play. Now it is done by professional actors [trained to] create links with support groups for positive women wherever we tour.” Old African connections yielded a good bit of activity on LPW2020. I met Oma Elzubair when we both worked for the ‘mother of forced migration studies’, Barbara Harrell-Bond in Cairo; Oma is now back in Khartoum (Sudan). She will blog about a range of local activities in Khartoum she’s conducting for LPW2020. And graphic designer, Adham Bakry (Cairo/Port Said, Egypt) made two Arabic versions of the LPW logo in conversation with Oma in Sudan.

Our goal for the next 14 days is to feature mostly articles by women, but also work by others in honor and support of women. On February 2nd, the day Yemanjá (goddess saint for fishers) is celebrated in his home region of Bahia, artist Thiago Correia Gonçalves shares three specially-designed posters (EN, PT, ES) for LPW2020.

Making an HIV-related project brought me back in touch with an old friend, Emanuel Brauna-Lechat who is making a film on access to healthcare for people of color in Brazil entitled, Dora Não Cansou de Viver… In his second piece for LUV he interviews its lead actress, Momô de Oliveira. We start the series with ‘Feasting with Panthers (and Palestine): Edmund White’s Jean Genet’ by Sarah Schulman. Sarah wrote this piece on the occasion of Edmund White’s 80th birthday. This is her third piece on LUV, including What Does a Queer Urban Future Look Like? and more recently, ‘People in Trouble’ at Thirty: On Realism, Trump, and the AIDS Cataclysm. In the same direction, we invited Cadu Oliveira to comment on LGBTI / HIV activism in the present political climate of Bolsonaro’s Brasil. Our LPW2020 series ends with a Field Note from Paula Nishijima for the Think Twice Collective based in Leiden (Netherlands).

Here’s a table of contents. We invite you to follow along and join us in celebrating LovePosivitveWomen2020!

*Pre-teaser: New versions of LPW logo in Arabic, Portuguese & Spanish by Adham Bakry & Gustavo Marcasse (Jan 31)

(1) ‘Feasting with Panthers (and Palestine): Edmund White’s Jean Genet’ by Sarah Schulman

(2) ‘Bobó for Yemanjá’ by Thiago Correia Gonçalves

(3) ‘Maidei’, Synopsis + Scene 1: Choose Life Women’s Group (Bulawayo)

(4) Emanuel Brauna-Lechat interviews Momô de Oliveira

(5) ‘Maidei’, Scene 2: Choose Life Women’s Group (Bulawayo)

(6) Interview with Cadu Oliveira on LGBTQIA+ organizing in São Paulo

(7) ‘Maidei’, Scene 3: Choose Life Women’s Group (Bulawayo)

(8) ‘Behind the Curtain’ by Iman (with Ankh Association)

(9) ‘Maidei’, Scenes 4 & 5: Choose Life Women’s Group (Bulawayo)

(10) Blog from Khartoum by Oma Elzubair

(11) ‘Maidei’, Scenes 6, 7, 8: Choose Life Women’s Group (Bulawayo)(12) Daniel Santiago Salguero interviews Jacqueline Sanchez for Luciérnagas

(13) ‘Maidei’, Scenes 9, 10: Choose Life Women’s Group (Bulawayo)

(14) Field Note from Paula Nishijima

*Post-teaser: A special surprise from one of my favorite graphic novelists, Power Paola at the end of LPW2020

What I’m learning about participatory art; #LPW2020, pre-B & Elpenor method, #2

This year Love Positive Women is so big for us it constitutes an ACT … Act 1.5 to be exact. The acts are dramaturgically useful for steering Luv ’til it Hurts toward its endpoint in mid-2020, and in that way reveal various ‘assemblages’ (or intense clusters) along the two-year course. While the ‘business plan’ of ACT II is about to be revealed (around Feb 14) with a graphic poster by Brasilian illustrator, chef, Umbandista and cat lover, PogoLand (who says artists don’t make worlds?), the co-making of activities in São Paulo, Khartoum and NYC for Love Positive Women 2020 and sequencing 14 days of women-authored and -focused online content took on a life (or ‘act’ as it were) of its own. Working with Canadian artist, Jessica Whitbread and using her ‘open source’ model for the Love Positive Women fourteen-day holiday has been a labor of LUV. And as such, we’ve learned some things. When we first started talking about her work in 2018, Jessica sent me the 2018 Love Positive Women holiday implementation guide (please download and use). I have written before on the LUV site about making (or why making) an ‘open work’, which is a reference to Umberto Eco’s writing at length on the prospect. Whether duration is called out by name or not, an open or open source work must consider duration and endurance. And, I think, whether it is growing in the intended direction over time. I’ve made three durational, rights-themed, multi-stakeholder projects for 10, 5 and 2 years respectively. So, I am familiar with the vernacular and semantics–and a new phrase, ‘articulation curve’–involved in the creation of a long-term project, and in this case a new 14-day holiday to celebrate positive women.

There has been a ‘turn’ within participatory art toward generosity. I imagine that generosity in terms of activism predates the art terms, so I won’t attempt to historicize the nuances of gesture, participation and generosity–e.g. giving away something at the museum and/or the less tangible offering of hospitality–at this point. Even if I find it extremely interesting. The other day at MASP, George and I picked up blank white posters with black trim from a Felix Gonzalez-Torres piece and we found ourselves talking about gestures and offerings. I was already working on LPW2020 at the time and I considered Gonzalez-Torres’ offerings to the public: a poster, candy, etc. The audience or public go away with something, and it’s supposed to create a reaction. It doesn’t quite tell one what to do though, or instruct (require) a return (reciprocal) gesture.

Love Positive Women is a more direct question or prompt: Will you consider poz women in these fourteen days running up to the North American Valentine’s Day (Feb 14). As a North American (gringo) living in Brasil, I realize that this big place doesn’t use the same date for romance; Dia dos Namorados is celebrated on June 12 because of its proximity to Saint Anthony’s Day on June 13. It basically uses another catholic marker than North America and Europe, but thankfully the days, 1-14 February fall just before carnival, and there is nice warm weather and a festive atmosphere.

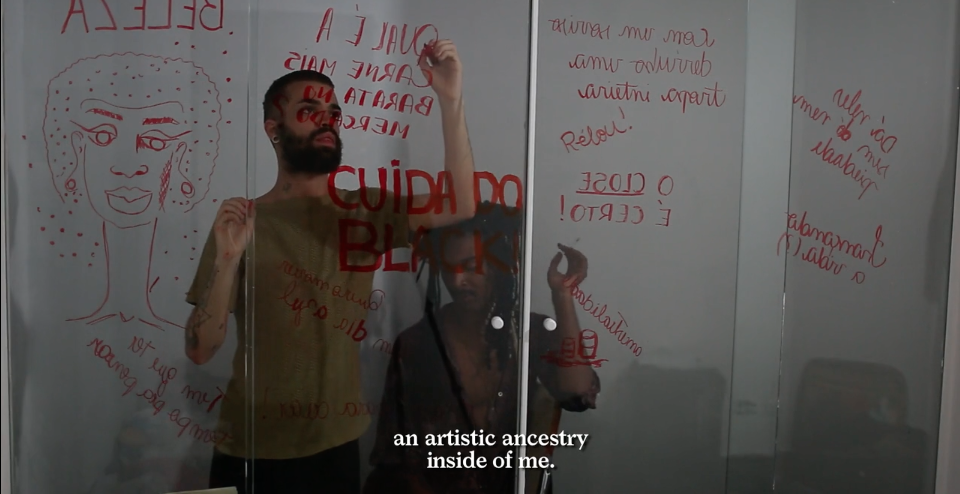

Over the course of making Luv ’til it Hurts, I’ve been able to witness the works of other artists in different parts of the world. In Bogotá I got to be a part of the final act or performance for Luciérnagas, a project led by Daniel Santiago Salguero that includes a majority of poz folks who are not artists. In this and other contexts the introduction of art concepts can be lost. Like getting together in solidarity to raise awareness on HIV is central, and that it is an art project for one person takes a backseat. Art becomes a minor subject within a bigger deal. While through an art lens, Luciérnagas contains elements of visual/conceptual art, performance and theatre, it stands as a transferrable, flexible mode of community organizing that was created using art terms and art funding. Because I make interpretable (enter-able) projects, I understand the intentions of Love Positive Women (or rather actively synthesize what I learn from Jessica’s work into broader considerations on participatory art). Given that LUV works with poets and others for whom visual/conceptual art terms can be foreign, we ran into some confusion. For example it was not entirely clear to an HIV+ poet how one conceptual ‘group’ project (Luv ’til it Hurts) could participate in another conceptual ‘group’ project. In this instance (and as a man), it would have been more beneficial to put the two HIV+ women artists in direct contact. However, that was not something I had time to do before the implementation of LUV’s workplan for LPW2020. In this instance, I felt that part of the confusion was my gender (somehow). Like why would a male artist with another project be pushing a female’s art project that focuses on women? I felt that perhaps my own intention of generosity was not understood. In the end, a planned event with the poet was scrapped, but the conversations gave way to a new idea, which was a focus on spaces that anyone can use. We decided to ‘outfit’ (or style) a couple cultural spaces in São Paulo’s Center with language-appropriate materials and design on the Love Positive Women (Amem Mulheres Positivas) movement. This plan reaches the publics of the spaces during multiple events (in each) from February 1-14, 2020, and encourages women to use the spaces year-round for support groups and cultural activities.

There were a few other ‘slow downs’ in our LPW2020 planning as well. For example, a trans woman asked me if I felt that she and I (poz folks) could make an event for poz women. Her question is great because it points to some issues (like vertical transmission) that had not affected either of us. But my answer is yes, I do. Still. In that conversation as well as another one just yesterday, the issue of payment came up. On one hand, I have a quick reaction that ‘no one is paying me’ but on the other–and in relation to how scarce cultural funding is today in Brasil–I understand. Funding is an issue that pervades HIV culture work. It is one that the LUV project is concentrated on. LUV plans for Amem Mulheres Positivas 2020 is all in place and with this moment to reflect, I think of a few other participatory projects I’ve had the chance to be a part of over the years–Human Hotel, HomeBase Project and Publication Studio–and how they might have clued me in to Jessica Whitbread’s work on Love Positive Women.

Cidade Queer, a film

Watch: Queer City / Cicade Queer, by Danila Bustamante.

Bodies that listen, dance, resist, manifest and become visible in our contemporary city. Bodies that dance the sounds of funk music, rap, samba, voguing, waacking, among other sonic styles of contestation, resistance and struggle. Through talks, dinners, experiences and exchanges, a city seeks to discuss how we live, work, share and survive the different LGBT+ stories and realities. The mini-documentary “Cidade Queer / Queer City”, directed by Danila Bustamante, takes its name from a 2016 site-specific, collective curatorial process in São Paulo, Brazil.

—

[*The Cidade Queer film was made from footage of the last two weeks of a year-long project of the same name. The Canadian foundation that partially funded the Cidade Queer project decided to fund a film on it during their site visit and the closure of the year-long project. Recently when I was making my artist profile on the Visual AIDS website, and receiving help from a staffer, I was asked how the Cidade Queer film is related to my own art work. Because I’m currently making a ‘multi-stakeholder, rights-focused, durational’ project on HIV and stigma, perhaps it was a good opportunity to explain how I work to a respected organization. This ‘multi-stakeholder, rights-focused, durational’ way is how I’ve done things for almost 20 years now, starting with freeDimensional. Lately, a colleague, Ismar Tirelli Neto and I have been discussing the idea of ‘minor literature’ proposed by Deleuze and Guattari, and from it I get some ideas on ‘minor production’. Over this 20-year period (of my art practice), I’ve made a few things that don’t get my name directly stamped on them. And the Queer City film–within the Cidade Queer project that was within Lanchonete.org–is a useful ‘item’ to dissect and analyze for this. The film and these memories are tagged in Field Notes because they offer me an opportunity to reflect on broader questions on ‘crediting’ at the intersection of art worlds and social justice frontiers. xo todd]

INGABIRE “Gift” (2005); #LPW2020, pre-A

Watch: INGABIRE “Gift” (2005), by Jesse Hawkes.

For its first Rwandan Film Festival in 2005, the Rwanda Cinema Centre helped several young directors and groups of actors to make films on important issues in Rwanda. The film “Ingabire” was based on an original musical theatre piece that was created by a group of high school students at an HIV Prevention conference earlier in the year. It was based on true stories from their lives and lives of their friends. The film still resonates today. During a recent Global Youth Connect workshop, I showed this film and the participants insisted that “stigma against people living with HIV does not exist in Rwanda today.” Little did they know that there was a GYC delegate from Rwanda standing in that room who didn’t disclose their status among these peers for fear of stigma. Apologies for the subtitles, but we created it in two days, and English was not one of the key languages of the staff at that time. Rwanda has since shifted from French to English as its official second language of instruction in schools after Kinyarwanda, which is the language you hear in the film.

[*When I wrote the piece, remembering my first AIDS work, which proceeded to ‘remember’ all my HIV/AIDS work, I actually forgot an important episode, which is when I first met Jesse Hawkes in Kigali (Rwanda). Jesse was there working on a project he founded called Rwandans & Americans in Partnership Contre SIDA /RAPSIDA, and I was helping to start a film festival. I studied film and remembering first meeting Jesse in Rwanda, I can easily remember the excitement and momentum that took me all over the African continent researching 3rd Cinema when I was in my twenties. I helped make a young filmmakers workshop (in which INGABIRE featured) during the inaugural Rwanda Film Festival, an idea I co-created with Rwandan filmmaker and founder of the Rwandan Film Center, Eric Kabera after meeting at the Zanzibar film festival in 2003. Ahhhh … nostalgia. Fast forward to September 2016, I am reminded of the documentation of the last month of a year-long process, Cidade Queer in São Paulo, and the eponymous film it generated at the hands of filmmaker Danila Bustamante. Jesse Hawkes is helping to make an event for Love Positive Women in NYC on Feb. 9 called ‘Bobó for [LUV] Iemanjá’, which is a part of Luv ’til it Hurts celebration of Love Positive Women 2020. xo todd]

What Does a Queer Urban Future Look Like?

[ *Back during the making of Cidade Queer (an inquiry opened by Lanchonete.org), I got the chance to ask some colleagues their views on queerness and a right to the city. I asked Sarah Schulman if ‘the urban’—yes, cities as well as urban encounters…but also the space and right(s) to live in, work in, and share the contemporary city—is an important source or reference for her work? Jose Esteban Muñoz begins his book, “Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity” (2009), with these words: “Queerness is an aspiration toward the future. To be queer is to imagine better possible futures.” So I guess what I’m asking is what a queer urban future might look/feel like to you? xo, Todd ]

Obviously, great cities are in terrible trouble as gentrification homogenizes their souls. However, there are still some core experiences of difference that make a place like New York City a center for the production of new ideas. After all, it is the mix that signifies urbanity, the irrefutable knowledge that people are different, which is built into real city living. In some places people wake up in privatized houses, they walk through their front doors and step into cars, and then drive to work and park.

This twice-a-day seminal experience is one of isolation and repetition. But waking up in an apartment building means recognizing your neighbors’ realities: who was fired, who is sick, who is in love, who can’t control their drug use, whose kid has finally gotten a job. By the time you get outside, there is already the knowledge that other people are real. Then, we walk through the neighborhood, see which businesses have been driven out, what new chains are devouring territory, which brave independent entrepreneurs are trying something new, waving, avoiding, chatting, making amends. Jump on the subway, where the knowledge that people suffer, have contradictions and need support is always present. And finally, get to work. This is an experience of recognizing difference. Of having to think about other people, notice them, and maybe even talk. This engagement is the source of great inspiration.

I have written so many books about the people in my building, my neighborhood, on the subway, on the street. They embody my life and my pages. So, when I imagine a future for myself and for my city, they are inseparable. My city is part of my heart, not something to drive through on the way. And New Yorkers love to talk to each other. We practice recognition. Recently, I have come to understand, profoundly, the difference between provincial cities and really urban ones: the range of communities.

In NYC, if you burn out on one queer, black, arts community, there are actually several other queer, black arts communities to connect with, and all the other larger communities that also include queer and black. There isn’t one clique controlling experimental film. There are many. While of course, being on the outs with those in power can be awful—just the worst—the machine is just too big to stay stagnant. And while some people are afraid of speaking back to power, plenty are not. When I see what kind of group bullying goes on in smaller places, where queers and artists act like In The Heat Of The Night, or those realist horror films where all the “best” citizens are secretly in the Klan and there is no escape, well, in NYC, there is always an escape. And what that means is that we have the freedom to change. Despite gentrification, there are still subcultures, substructures, undergrounds—some of which desperately want to be recognized, and others which absolutely don’t. There are hundreds of dance scenes, multiple ethnicities of Chinese, everything you could ever want to eat, more musicians than there are places to hear them, the greatest actors in the country, and beauty at your fingertips. There is the petty and there is the very deep.

“Queer” is a category in flux, and urban queer is on a huge continuum. We have the banal, the spoiled, the exploitative, the boring. We have the expansive, the inquisitive, the creative, the open hearted. We have the consumer, and the producer. We have the new abject object, the new queer: the undocumented, trans*, HIV positive, the queers whom the police shoot to kill. We have those of us who are not in families, and therefore not the ideal consumer, the community-based queers, who share a public space, and the privatized queers who put their citizenship first. Right now, everything “queer” that has a place of honor is somehow rooted in the family. Just this year in media: Transparent, Fun Home, The Argonauts, even Carol—who, in the book, was somewhat repulsed by her child, but in the film became a mother, giving that famous plea for tolerance speech that is required by the tolerant.

But what about the rest of us? Where are we? Looking around, I see queer in the leadership of Black Lives Matter and the new Black Student Movement. I see queer inside Palestine Solidarity. I see a place for queers who have an agenda bigger than their queer selves. And for the rest, I see an invitation into the status quo. And some of us are inside each room. And some of us don’t have a room as the city struggles to find homes for its own children. There is a building on 57th Street in which every apartment is a floor through and costs 100 million dollars. Real estate is like a security box for some of the globe’s elite. It’s a safe place to put your money. East New York was offered graduated income housing, but it’s not a graduated income neighborhood. We need 500,000 housing units to save our soul. At least we know the terms of the goal. We need to be rescued and to save ourselves. The homogenized lose consciousness, and don’t understand the fight. But it only takes a critical mass to make the change. A new society is literally being built on top of the old. All extant housing stock is already claimed; now, they are constructing towers without public aspects: no hospitals, no schools, a heliport on a building’s roof. And yet, my over-crowded classroom has 16 nationalities. My job is to open their hearts.

________________________________

*To read 10 more responses to ‘What does a queer urban future look like?’, click here.

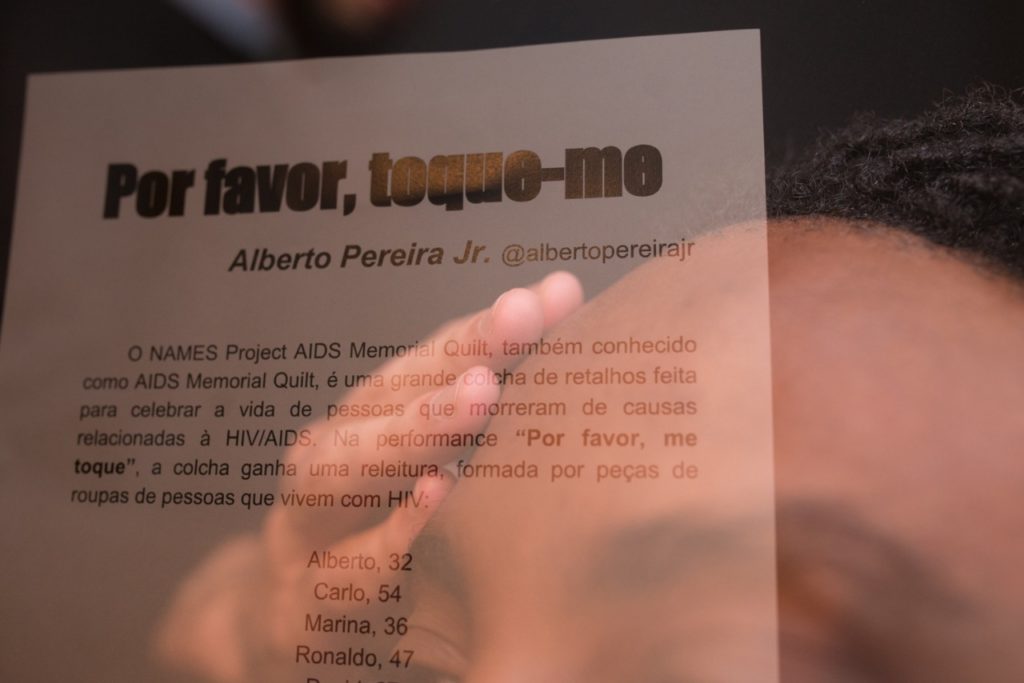

Please, touch me (PT/EN)

[*Alberto Pereira Jr. first made ‘Please, touch me’ for a 2019 workshop in São Paulo. His production notes are the third in a series that also includes a project abstract #movingtarget and creative writing, ELE. xo, Todd]

PT

Instigado por um workshop realizado no instituto Itaú Cultural, sobre estigma e produção artística contemporânea em relação ao tema HIV/Aids, realizei a minha segunda saída do armário: vivendo há 10 anos com HIV, criei a performance “Por favor, toque-me”, revelando meu status positivo e convidando o público a ressignificar a imagem pré-concebida de um corpo positivo.

EN

Instigated by a workshop that was realized in the Itaú Cultural Institute, on stigma and the contemporary artistic production in relation to the theme of HIV/Aids, I realized my second coming out of the closet: living with HIV for over 10 years, I created the performance “Please, touch me,” revealing my positive status and inviting the public to resignify the preconceived image of a positive body.

PT

A performance-instalação “Por Favor, Toque-me” reelabora, no contato entre criador/performer e público, as possíveis imagens pré-concebidas a cerca de um corpo que vive com o HIV. Característica ou estigma, a soropositividade de Alberto Pereira Jr., é autodeclarada em seu vestuário, tornando-se física e passível de toque. Tocar para apreender, para expurgar, para reumanizar? Cabe ao público participante investigar suas novas ou antigas convicções. Integra a parte instalativa da performance, um tapete costurado tal qual uma colcha de retalhos, com peças de roupas de pessoas que vivem com HIV.

EN

1) Activity title: Please, touch me

a) Objectives: The performance/body work “Please, Touch Me” re-elaborates, in the contact between creator/performer and audience, the possible preconceived images about a human body living with HIV.

b) Description of activities: Characteristic or stigma, the seropositivity of artist and activist Alberto Pereira Jr. is self-declared in his clothing, becoming physical and susceptible to people’s touch. Touch to seize, to purge, to rehumanize? It is up to the participating public to investigate their new or old beliefs about human relations, about HIV and the prejudice that follows people

living under this stigma.

c) Material: There is an installation part of the performance, a rug sewn like a quilt, with garments of people living with HIV, inspired by the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt.

d) Format: The performer’s body will be touched and he will touch as well the people who touch him. The encounter between the audience and the artist will provoke a new narrative of infinities possibilities.

e) Expected Outcomes:Wherever the performance is performed, it generates empathy, listening and affection. A moment of resignification of preconceived ideas from the public and also of empowerment for the artist, who has been living with HIV for 10 years.

f) Experience/expertise: Alberto Pereira Jr. is a Brazilian social artist, who seeks intersection between theater, audiovisual, body work and literature for a dialogue and friction of contemporary themes such as blackness, homosexuality, HIV and affectivity. He created and directed “I now pronounce you…” (2012), documentary about LGBTQI + families in Brazil, awarded and funded by the São Paulo State Secretariat of Culture. Born and raised in the outskirts of São Paulo city, he is the founder of Domingo Ela Não Vai, one of the biggest street Carnival groups called blocos, part of the official line-up of the city. He also organizes various cultural events, such as Queermesse, a party that reunites LGBTQI + collectives. He created Subtle Lashes Festival of Margins Arts, sponsored by Levi’s. In its first edition, held in April 2019, the festival had a line-up with only black, trans and cis women, LGBTQI+ community protagonism, with music, talks and free workshops. As a journalist, he worked for six years at Grupo Folha Publishing Co., one of the biggest Brazilian media outlets. Currently, besides performing in theater, he has been working as a screenwriter and creative manager for TV and film projects, producing content for Discovery Channel, MTV, Fox and others.